News archive

Reports

- Details

- 15 May 2013

Cave man met shrimp man! A visit to Kent’s Cavern, Torquay

16 September 2023

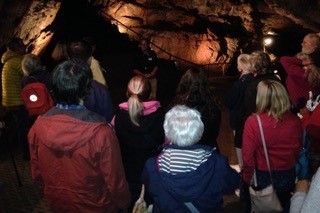

For almost half a million years people and animals have visited and sheltered in Kents Cavern. In September of this year, 26 members and friends visited these caves and were given a guided tour to explore them. The cave temperature remains at 14 degrees celsius throughout the year which feels cold in summer but warm in winter. Walking through semi-darkness, the calcite formations of straws, curtains, columns, stalactites, flowstones and stalagmites took on an eerie and impressive sight.

At least 350 thousand years ago a thick stalagmite floor formed and sealed in earlier layers along with the flints and bones within them. Interbedded between layers building up were the remains of animals and humans that inhabited the cave and surrounding area during the last ice age; these included bears, lions and foxes, badgers, wolves and hyenas - especially hyenas that used the caves to live and breed. Importantly, the hyenas brought food into the caves, bones had been found of deer, horse, woolly rhinoceros and woolly mammoth. Further evidence of extinct animals included cave bears, cave lions and scimitar cats. We were led from one chamber to another until we reached the Bears Den where a cave bears skull is embedded in the ceiling. Whilst in here all lights were diminished for some time, creating an unforgettable blackout experience.

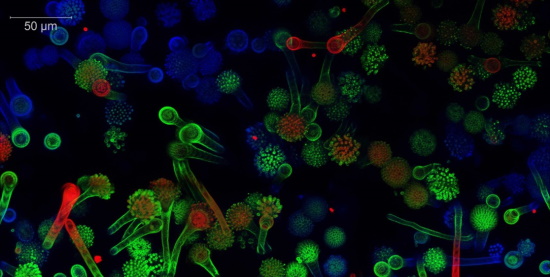

We also came to investigate a very small troglophile still living in the caves, a tiny freshwater shrimp Niphargus glennii, an English endemic only known from Devon and Cornwall. Dr Lee Knight, a freshwater ecologist, set up a mini laboratory in the Cavern Cafe. These tiny live transparent shrimps were examined microscopically and Lee gave us some background information about subterranean habitats and shrimp structure, adaptation and behaviour.

We also came to investigate a very small troglophile still living in the caves, a tiny freshwater shrimp Niphargus glennii, an English endemic only known from Devon and Cornwall. Dr Lee Knight, a freshwater ecologist, set up a mini laboratory in the Cavern Cafe. These tiny live transparent shrimps were examined microscopically and Lee gave us some background information about subterranean habitats and shrimp structure, adaptation and behaviour.

Lee was a great enthusiast and answered our questions with patience and detail. We are so grateful to him for his time and care in setting this up – I believe he was up very early in the morning to catch our specimens. Our thanks too, to Simon our wonderful guide in the caves. We did, of course, end with a Devon cream tea.

First photograph - the group being taken on a tour of the cavern. Credit: Bruce Selkirk

Second photograph - Lee Knight’s Pop-up Laboratory plus attendees, to view the shrimps. Credit: Bruce Selkirk

Christine Fry MRSB

Visit to Clinton Estates, East Devon

17 June 2023

Our group gathered at the Arena Office, Bicton Park, for a presentation and site tour of the Lower Otter Restoration Project (LORP). The visit was led by Dr Sam Bridgewater, Head of Wildlife and Conservation for the Clinton Devon Estates.

LORP is an ambitious project with the aim of recreating about 55 hectares (136 acres) of intertidal wetlands that currently comprises a mixture of farmland, common land and amenity areas such as a cricket club and footpath for walkers. The project is aimed at protecting the Otter Valley from the estimated 1m. rise in local sea levels, over the coming decades, due to climate change. Such a rise would inundate large areas of valuable land, if not carefully planned-for and managed.

Clinton Devon Estates (CDE) is the largest landowner in Devon and has a wide range of land and property interests. In addition to about 34 farms covering around 7000 hectares, CDE has woodland, heathland and amenity areas such as sports fields and Bicton Park with its equestrian area, under management. It also owns and manages mixed residential properties and industrial estates, which employ about 1500 local people. CDE therefore has the strong local presence and financial strength to undertake such a huge task and sees the need to liaise with all interested parties as a key part of the LORP initiative.

LORP is being led by the Environment Agency in partnership with CDE and several other UK-based organisations and has a budget of about £22mio with substantial funding (nearly 70%) from the European Development Fund. As such, learning points from the project will be shared with other, similar mainland European projects such as that in the Saane Valley, Normandy which is part of an overall initiative to pre-empt climate change and provide 100ha of protective coastal wetland.

The event went very well, with a good mixture of attendees. Our thanks go to our host Dr Sam Bridgewater and to our branch secretary Christine Fry who organised this event.

Brian Selkirk

Killer Fungus

14 November 2019

Professor Neil Gow FRSB, deputy vice chancellor for research and impact at Exeter University, is a dedicated mycophile. His presentation to around 150 RSB members and guests included glorious photographs of ‘beautiful’ fungi – from honeycomb and coral, to Fly Agarics and Destroying Angels, Ink Caps and Devil’s Fingers – testifying to his passion. He informed us that there may be as many as two-five million species of fungi (compared with less than half a million plant species).

Up to 60% of trees are weakened, killed and consumed by fungi, releasing billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which briefly inspired me to continue uprooting honey fungus (Armillaria) fruiting bodies in my garden, until he superimposed a single organism (a clonal colony of A. solidipes measuring 3.5km in diameter) on a map of the city of Exeter.

Aspergillus. Image supplied by Professor Neil Gow FRS FRSB

Professor Gow’s research is primarily directed to medical mycology. Around one in four of us at any one time has a superficial fungal infection resulting in common, and treatable, conditions such as athlete’s foot, scalp ringworm and thrush. As the lecture theatre lights dimmed, Professor Gow shone a light onto the darker side of fungi, particularly those that contribute to an estimated one million human deaths each year. The incidence of invasive and fungal infections is, fortunately, much lower than those with mild pathogenicity, but Professor Gow showed that in some instances poor diagnosis and delayed onset of treatment can have chronic and frequently fatal outcomes. Surprisingly, given the widespread and devastating effects of many fungus species, less than 2.5% of medical research spending in the UK and USA is committed to mycology, compared with 45% for ‘cancer’. Exeter University has a long history of fungal biology research, and now hosts the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, boasting a World-leading collection (a mycelium?) of fungus experts. Professor Gow’s talk was entertaining, informative, inspiring and thought-provoking and those present left with a little more respect for ‘killer fungi’.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB

Biology Week: Marine Turtles and Climate Change

9 October 2019

This public lecture was organised by Dr Rich Boden FRSB and his colleagues at Plymouth University. The lecture featured as part of Biology Week and attracted almost 300 attendees. Professor Annette Broderick from Exeter University’s Cornwall campus at Penryn spoke engagingly about her work with marine turtles over the last ‘twenty-something’ years. Her work has been mainly with populations of Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and Green (Chelonia mydas) Turtles nesting on Cyprus, but she also presented data from sites on Ascension Island – turtles choose nice beaches!

She introduced us to ‘pivotal temperature’, sex ratios, and egg-laying depths as well as to the impossible task of visual sex determination in turtle hatchlings. Professor Broderick did not shy away from presenting research data in the form of complex graphs, but she explained her team’s findings in such a way that the audience could grasp the significance of the findings.

As the gender of marine turtle hatchlings is temperature-dependent, environmental warming could be expected to have a catastrophic effect on turtle populations. We were presented with modelled data to show what could happen if sea temperature rises by up to 4oC, and then Professor Broderick explained several behavioural changes that have been observed, with one example being that egg deposition is now happening earlier in the year than when the team first started recording in 1992. This was not a “marine turtles are doomed by the action of mankind” talk. This was a balanced account of turtle nesting behaviour and population dynamics based on almost thirty years of field observation, recording and tracking. It was an inspirational talk for all the early career biologists who packed the lecture theatre.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB

Art in the Service of Science

16 March 2019

We’ve all seen the pretty and instructive graphics on the cover of Nature, Science and our own The Biologist, but we and the 25 other guests attending the branch AGM at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth hadn’t really given a thought to how they are created or, indeed, what medical and biological illustration involves.

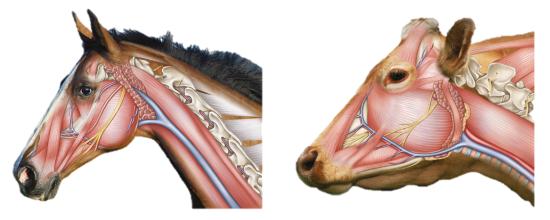

Our guest speakers were Debbie Maizels MRSB and Philip Wilson – both freelance and expert artists. Philip took us from the exquisite sketches of Leonardo da Vinci to the twentieth century world of the medical artist who would sit behind surgeons in operating theatres drawing surgical procedures. Why? Partly because artists ignore blood in the surgical field and because photography could not emphasise or selectively highlight certain features, such as deep cavities.

Since the 1990s computers and cordless pens have replaced paper and ink, and digital artwork can be easily amended, stored and sent instantly all over the world.

Credit: Debbie Maizels MRSB

Debbie’s work is mainly scientific and veterinary art, including those amazing cover illustrations. Complex datasets and involved life-cycles can be reduced to cleverly illustrated charts and imaginative visual representations. How else can you show a flea sitting on a dinosaur’s back?

Both speakers emphasised that knowledge of the subject is as important as technical competence, and this was well illustrated with Debbie’s dissection guides and anatomical studies.

Their talk ended with a chilling demonstration of how medical art can be used in court to show jurors in murder trials the trajectory of a bullet through a body or the angle of attack of a knife wound.

Next time you see a cover graphic try to spend a bit more time appreciating the skills of the artist who created it.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB and Mary Jenking CBiol MRSB

Darwin in Devon

12 February 2019

Charles Darwin lookalike, Doug Herdson, enthralled 30 members, their guests and several members of the Devon History Society with a talk about the naturalist’s four known visits to Devon. The venue for the talk was the Outer Library of the Devon & Exeter Institution, founded in 1813, which provided a fitting setting in which to celebrate Darwin’s 210th birthday on 12th February.

Darwin visited Devon twice in 1831, from where he departed Devonport on 27th December on board the survey barque H.M.S. Beagle commanded by Robert FitzRoy. His journal recorded that, “These two months at Plymouth were the most miserable which I ever spent, though I exerted myself in various ways”.

Doug reported that the voyage, expected to take 1½ to 2 years, took almost five years and that Darwin’s third visit to Devon was a two-day dash across the county en route to his family home in Shrewsbury in October 1836 as soon as the Beagle docked in Plymouth.

I n the following two decades Darwin worked on his journal, wrote a treatise on barnacles and developed his theory of natural selection. Origin of Species was published in 1859 and Darwin made his fourth and final visit to Devon – to Torquay – in 1861. He spent six weeks in, “the most opulent, the handsomest, and the most fashionable watering place in the British Isles”, where he made observations on native orchids and the mechanisms by which insects fertilise the flowers.

n the following two decades Darwin worked on his journal, wrote a treatise on barnacles and developed his theory of natural selection. Origin of Species was published in 1859 and Darwin made his fourth and final visit to Devon – to Torquay – in 1861. He spent six weeks in, “the most opulent, the handsomest, and the most fashionable watering place in the British Isles”, where he made observations on native orchids and the mechanisms by which insects fertilise the flowers.

Doug Herdson, Charles Darwin lookalike

Although Darwin wrote about “horrid Plymouth”, Doug Herdson showed that he clearly revelled in the natural beauty of the county and the company of some of the people he met. We enjoyed our celebratory birthday cake in the knowledge that Devon touched the life of one of the most influential naturalists of all time.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB

Behind The Scenes At Dartmoor Zoo

18 September 2018

After a night of gales reaching 60 miles an hour, when we feared our trip to Dartmoor Zoological Park might be cancelled, an intrepid group of RSB members braved blustery conditions and gathered in the welcoming café and visitor centre at the start of an amazing day out. We really did go ‘behind the scenes,’ thanks to Coral Jonas and Mitch Walker, who were both incredibly enthusiastic, generous with their ‘insider knowledge’ and prepared to answer all of our questions.

Highlights of the day included scratching an incredibly chilled Brazilian tapir behind the ears while discussing her contraceptive programme, stroking wolves while considering the difficulties of keeping older animals in zoos, learning how to keep a jaguar intellectually stimulated, and getting to grips with Amur tiger breeding programmes.

Our outdoor adventures were followed by indoor encounters – holding a chameleon was an absolute highlight of the day, along with seeing incredibly rare golden mantella frogs (but not the frogspawn they have produced!) and a lesser hedgehog tenrec – cute enough to charm every biologist in the room!

Following a delicious and plentiful lunch, we listened to Benjamin Mee, the owner of Dartmoor Zoological Park. He gave us a very personal and intimate insight into the events surrounding his purchase and development of the park, laced with considerable humour and some amazing anecdotes – his story having formed the book We Bought A Zoo, which was turned into a film of the same name starring Matt Damon and Scarlett Johansson in 2011.

Finally, we were free to wander around at our leisure to the end of the day. It was a well organised and delightful visit to a fascinating venue in a beautiful part of the country - I’m sure everyone who came along will have learned something – and will remember the trip for a very long time.

Ann Fullick MA FRSB

Life On The Yealm Bioblitz (Regional Grant Scheme Event)

15 July 2018

The Yealm estuary in south Devon was the subject of the 10th annual BioBlitz organised and coordinated by the Marine Biological Association of the UK.

With ancient woodlands flanking the river, freshwater and brackish creeks, seagrass beds, sandy and rocky shores as well as sea cliffs, there is a great diversity of habitats here. Add in an amazing 420 people from the local community and elsewhere in the southwest, it is unsurprising that over 855 species were recorded in the 29-hour marathon recording session in mid-July 2018.

Though principally supported financially by the Heritage Lottery Fund, an award from the RSB’s Regional Grant Scheme helped to fund the programme of events, including the Citizen Science Showcase held at the Base Camp on Saturday 13th October during Biology Week.

Awards were presented for some of the best photographs and sound recordings taken during the BioBlitz, including to 14 year old Bella Leal for her stunning image of an Eurasian blue tit seemingly frozen in space.

Over 40 sponsors and partner organisations participated in the initiative and the 6 month report can be accessed at www.mba.ac.uk/citizen-science#b15

Congratulations to Dr John Green and his team at the MBA and to everyone in south Devon who contributed to this important biological survey.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB

Visit to Looe Island

26 July 2018

St George’s Island (Looe Island) is a 22-acre nature reserve located a short boat trip away from the pretty Cornwall village of Looe. Owned by Cornwall Wildlife Trust (CWT) since 2004, the island is home to a wide variety of species including grey seals, gulls, oystercatchers, fulmars and, at least in 2018, sixteen species of butterflies have been recorded.

A small group of RSB members and local marine conservation volunteers spent three hours in glorious sunshine on this tree-covered haven in the company of resident wardens Jon Ross and Claire Lewis. The group were treated to a guided walk and slide show, covering the island’s early occupation by Romans (the island was excavated by Time Team in 2009), and its more recent, delightfully eccentric, owners including a retired army officer who fired warning shots to dissuade visitors, and the Atkins sisters who bequeathed the island to the CWT.

Although only 1 mile across the Whitsand and Looe Bay marine conservation zone to the mainland, with the exception of a small flock of Hebridean sheep there are no terrestrial mammals (rats have been eradicated) or reptiles on the island, although smooth newts have been found.

We saw Gatekeeper (Pyronia tithonus), Ringlet (Aphantopus hyperantus) and Holly Blue (Celastrina argiolus) butterflies as well as more commonly encountered lepidopterans on flowers in the extensive vegetable garden, which is planted with Kiwi fruit, walnuts and grape vines in addition to artichokes, parsnips and seaweed-mulched new potatoes.

Seabird life abounds and large numbers of Shags and Great Black-backed Gulls were evident, plus Rock-Pipits and even Little Egrets were observed. This was a glorious way to spend an afternoon and we thank Jon, Claire and CWT for the opportunity.

Dr Ian Varndell CBiol FRSB

Plant Fascination Day 2018: Helping The Pollinators

18 May 2018

Buckfast Abbey, completed in its current form in 1938, provided the stunning backdrop to our day visiting the Bee Department and gardens. Head Beekeeper Claire Densley gave an engaging talk, starting with a brief introduction to the Apidae.

Her description of virgin queens leaving the colony to fly to a drone congregation area to mate with multiple drones, before returning to the hive, was both amusing and amazing. The drones die after mating, but the queens may mate another fifteen times, storing the sperm for up to 5 years. Consequently, genetic diversity within a colony can be very broad, proving advantageous to the colony’s resistance against pathogens.

Buckfast Abbey gained worldwide fame as a result of the work of Brother Adam, who was Head Beekeeper from 1919 to 1990, and who developed the ‘Buckfast Bee’ by crossing numerous different strains producing a high yielding, docile bee. He took drones and queens to remotest Dartmoor to mate where they would not encounter other bees. Pure breeding, however, makes the variety susceptible to disease and the Department at Buckfast decided to return to local breeds with increased genetic diversity. The Department has also moved away from intense honey production, and now uses their 40 hives as a teaching resource.

Buckfast Abbey gained worldwide fame as a result of the work of Brother Adam, who was Head Beekeeper from 1919 to 1990, and who developed the ‘Buckfast Bee’ by crossing numerous different strains producing a high yielding, docile bee. He took drones and queens to remotest Dartmoor to mate where they would not encounter other bees. Pure breeding, however, makes the variety susceptible to disease and the Department at Buckfast decided to return to local breeds with increased genetic diversity. The Department has also moved away from intense honey production, and now uses their 40 hives as a teaching resource.

Major pollinator threats include parasitic diseases and farming practices with vast areas of land being used for monoculture (the image of Californian almond plantations was horrifying). Diverse planting lies at the heart of the planting within the Abbey gardens.

Head Gardener Aaron Southgate outlined his philosophy on the use of natural fertilisers, such as his compost tea made from bubbling non-chlorinated water through composted materials to harvest microorganisms, and pest control measures which included large quantities of vinegar!

The visit demonstrated the essential link between plant diversity and pollinator health and sustainability. See the Buckfast website for more information.

Dr Jonathan Ratcliffe MRSB

Obesity research – are we barking up the wrong tree?

19 April 2018

Our AGM was followed by a lecture given by Dr Phil Langton, senior teaching fellow at Bristol University. His talk gave an overview of the causes of obesity and the problems it can cause. He pointed out that too much food, lack of exercise, too much fat, excess sugar, the “wrong type” of gut bacteria, possibly lack of sleep and, more recently certain combinations of alleles – have all been blamed for an increase in obesity in the Western World.

In the 1960s only 10% of the UK population was thought to be obese, whereas now it is closer to 35%. We eat because we enjoy food and not necessarily because we are hungry. The spread of a Western diet to other parts of the world has been linked to a rise in obesity and an increase in the diseases associated with it.

Our hunter gatherer ancestors probably ate more complex carbohydrates with a slower release of sugars. Cereals and fruits were only seasonal and very little sugary food, like honey, was available.

The evidence suggests that a high sugar diet leads to rapid glucose intake, followed by a rapid rise in insulin production and fast removal of glucose from the blood, leaving us feeling hungry. The failure of many diets is due to an unacceptable feeling of hunger. This can lead to snacking and further episodes of insulin release.

Despite health warnings from the Government, the NHS and the media we still consume too much prepared food. Its sugar, salt and fat content is not always clear and frequently ignored. Dr Langton’s talk left us with much food for thought.

Mary Jenking CBiol MRSB

Joint meeting on the challenges of plant conservation

30 January 2018

Ian Wright, the National Trust's lead gardens advisor in the South West and Wales, began our meeting with the Devon Gardens Trust by saying that many of the plants we grow are under threat.

The risk of flooding has risen due to climate change and caused considerable damage at Bodnant Garden in North Wales in 2015, while Westbury Court in Gloucestershire is increasingly at risk of salt water contamination from the River Severn. The storms of recent years have resulted in the loss of many trees, although there has been good recovery in the South East.

Higher temperatures, our increasing population, different crops and new pests and diseases all take their toll. Horse Chestnuts are currently under threat from leaf mining moth, bleeding canker and leaf blotch.

Phytophthora fungus has attacked hosts as diverse as larch and rhododendron, though more have survived than was expected. Ash die back has also spread more slowly than predicted.

Some pests and diseases come in through our ports and seaports yet their inspection teams are expensive to run and undermanned. The Asian longhorn beetle arrived on wooden packaging sent to a quarry merchant.

The National Trust is building up a database of its plants, recording gains, losses and problems. New shrubs and trees must spend six weeks in quarantine before planting. The trust has a plant conservation centre near Honiton in Devon, away from people and forests to maintain biosecurity. Here different types of propagation are investigated including microbudding and the use of soil warming cables for grafting.

We are lucky in the UK to have 620 national plant collections which help to maintain and exchange plant stocks. The National Trust also works with Kew and the RHS to provide material for the Millennium Seed Bank, herbarium specimens and botanical illustrations. In future we may need to rely less on imported plants and be more vigilant about the health of the plants we grow.

Mary Jenking CBiol MRSB

Lecture and visit to the Norman Lockyer Observatory Sidmouth

9 December 2017

The Norman Lockyer Observatory at Sidmouth is home to an active amateur astronomical society, who were our hosts for the evening. Our speaker was Carol Boote, former lecturer of the Open University, who began by reminding us of the features which have allowed the evolution of life on Earth. With a 'Goldilocks position' relative to a stable star, Earth's iron core and magnetic field deflects charged particles from the sun and helps to retain our atmosphere. Plus, there is the size and mass of our planet, the presence of a moon and abundance of water.

Mars, by contrast, is smaller and colder, has no magnetic field and only a tenuous atmosphere. Yet information from our orbiters and landers suggest seasonal changes and the rock chemistry indicates past water. The Exo Mars Orbiter now in orbit is looking for methane and a new lander in 2020 will search for more evidence of life.

Amongst the moons of Jupiter, Europa holds the best possibility of life. It has a thick layer of water ice over liquid water, tidally warmed by Jupiter. It has a magnetic field, some salt in the water and a rocky interior. A new flyby is planned for the 2020s, followed by a lander. Titan has an atmosphere of nitrogen and methane. Evidence from Cassini's journey past suggests liquid methane lakes and dunes of hydrocarbons. Its atmospheric pressure at the surface is 60% greater than on Earth and is probably too cold for life.

Outside the Solar System, as of April 2017 there were 3,400 confirmed exoplanets. 15 are classified as habitable and 5 are considered by the SETI instutute (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) to be interesting. Cheops, an exoplanet satellite made by the European Space Agency, is launching in 2018 to look for transits of planets across stars. We still have no direct evidence for life elsewhere, but if we keep looking, maybe one day...

Mary Jenking CBiol MRSB

Gene Therapy - fact or fiction?

11 October 2017

In a first for me, and I suspect for many if not all of the large audience who attended this lecture at Plymouth University, Dr Simon Waddington embarked on an ambitious yet successful online interactive survey with 126 members of the audience. The survey asked how many of those present knew about gene therapy, would use it personally to correct physical or mental problems and, importantly, whether we would use gene therapy to correct problems in our germline so our offspring would not inherit them.

Simon’s explanation of how cells work, how viruses work and how we can ‘hack’ viruses was simple and clear for the audience of professional biologists, life science students, sixth formers and members of the general public alike. He challenged the audience to identify films that have portraying the use of gene therapy in various ways, such as to completely re-engineer the phenotype of a human, or release a super-virulent strain of virus. I won’t disclose the films in case Simon repeats this talk elsewhere, but you can sleep easily though – all the Hollywood claims were debunked!

Simon described his own work on haemophilia B and the enormous cost to the NHS of recombinant factors VIII and IX (£100K per patient per year) which could be circumvented with gene therapy. A major advance with the correction of X-linked severe immune deficiency syndrome (X-SCID) was reported by groups in London and Paris a few years ago, but in the trial a small number of ‘cured’ children developed leukaemia, which cast a huge shadow over this powerful therapeutic approach.

A long Q&A session followed Simon’s compelling talk, and one particular question struck a chord – could the effects of gene therapy simply wear off? Simon’s response was honest and clear – these are experiments on living human subjects – we simply don’t know what will happen. This powerful approach clearly has many hurdles to overcome and opportunities to explore.

Our sincere thanks to Simon, and to our hosts at Plymouth – Drs Mairi Knight, Rich Boden and Paul Ramsay for their wonderful welcome, hospitality and organisation.

Dr Ian M Varndell CBiol FRSB, branch chairman

Nature Walk from Lynmouth to Watersmeet

10 June 2017

Lynmouth, a pretty town on the north Devon coast, was devastated by flood water in 1952. Our party of sixteen was shown some black and white Pathé newsreels by our guide Julian Gurney, which illustrated the aftermath of the terrifying event.

Sixty five years later, on a drizzly but warm June day, we walked along the East Lyn river enjoying the babbling of the water and the infectious enthusiasm of our knowledgeable guide (you can follow him on Twitter @ExmoorNature).

L-R: Red-tailed bee on Green Alkanet (Pentaglottis sempervirens), Irish Spurge (Euphorbia hyberna)

The Watersmeet Valley is well known for its abundant plant life, and our attention was drawn to slender St John's wort (Hypericum pulchrum), cow wheat (Melampyrum pratense), herb robert (Geranium robertianum) and herb bennett (Geum urbanum), the rare Irish spurge (Euphorbia hyberna) and many other species, as well as to the antiseptic smell of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) root which we agreed reminded us of Germolene.

Gurney, an Exmoor ranger, is a very keen butterfly spotter and bee identifier, and as the weather was not really conducive for Lepidopterans other than a couple of intrepid green-veined whites (Pieris napi), every buzz was followed with interest. Lunch was taken at Watersmeet, now a National Trust tearoom and gift shop, formerly a hunting and fishing lodge. Grey wagtails, bluetits and various finches accompanied our group, awaiting tasty morsels.

One of the salutary lessons of the day was to witness the effect of innocent garden escapees out-competing the native and natural flora. Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) has been managed carefully and is now restricted to mid-river islands, but Tellima grandiflora and Crocosmia sp. (Montbretia) – both widely available in garden centres, are spreading along the banks of the river, crowding out more delicate species.

Our day ended with a 30 minute film of "Exmoor through Time" which was both interesting and highly informative. Enormous thanks are extended to Julian and his colleagues at the Exmoor National Park Centre in Lynmouth.

Dr Ian M Varndell CBiol FRSB

Making the Devon Bird Atlas – Mapping 30 Years of Change

14 January 2017

In 2013 the British Trust for Ornithology produced the third National Atlas of Breeding Birds in the UK, and the information from it formed the basis for the Devon Atlas. Our speaker, Mike Hounsome produced the maps, statistics and website.

The area sampled was 6707km2, surveyed by 1,200 volunteers who made 1.1 million records. Observations were made in one hour sessions, twice a year, and the two figures were combined.

Surveys like this are difficult to standardise, but the observers looked for various indications that breeding birds were present, including behaviour, song, nests, eggs or young.

The results show the percentage increase or decrease in the number of areas occupied by a species compared to earlier surveys, but not the actual numbers of birds.

Land coverage maps indicate the acreage of farmland, improved grassland and semi-natural grassland. ‘Improved’ means the removal of weeds and a reduced number of grass species, which is better for stock but affects the diet of birds such as the skylark and meadow pipit. This type of vegetation has greatly increased in recent years.

Big changes are seen in the distribution of some birds including lapwing and cuckoo. Starlings still breed over wide areas, but in far fewer numbers, possibly because there is less food for them in the improved grassland soils. Siskin are more widely spread in the south and west where conifer forests are maturing.

Monitoring such variations highlights the importance of the Atlas, especially now at a time of increasing change in our climate and the habitats around us. We were impressed by the dedication of the volunteers and the skill in processing and presenting so much data.

Mary Jenking MRSB

Dining with Darwin –How our food evolved and influenced our evolution

12 October 2016

The great apes and our ancestors were vegetarian. How and when did we become omnivorous? Professor Jonathan Silvertown from the University of Edinburgh, a world-renowned plant population ecologist, began his talk at the annual University of Plymouth RSB Lecture with an outline of our ancestors’ nutritional history.

At Olduvai Gorge there is evidence of megafaunal remains, including elephants, killed by Homo erectus 1.34 MYA (million years ago). We are unique in our social eating and this may have come from the co-operation needed to kill and share large animals.

Our increasing cranial capacity has been matched by our need for better nutrition. All known human cultures cook their food – our guts would need to be 40% bigger to just eat raw food. We have archeological evidence for fire making from 400,000 years ago and by 165,000 years ago shellfish and small mammals were part of the human diet.

We are gradually exploring the evolution of many of our foodstuffs. In the Andes one species of potato has given rise to all the varieties eaten worldwide, and all our cattle are descended from an extinct species of ox.

Artificial selection during the last 12,000 years has produced our modern chickens from red jungle fowl; sugar cane from wild grasses, and broccoli, kale and other brassicas from wild cabbage.

Over the last 2,000 years wheat has been selected for seeds that stay on the plant longer, so that fewer are lost during harvesting.

Agriculture and domestication of animals has also changed us. We use the enzyme lactase to help us to digest milk. It is produced by babies and also populations with a mutation which allows continuing lactase production. In Northern Europe this development occurred about 7,500 years ago. In Saudi Arabia, a different mutation allows the consumption of camel’s milk. Populations without such a mutation must ferment milk into yoghurt or cheese

Professor Silverton certainly gave us much interesting food for thought.

Mary Jenking MRSB

Devon Dragonflies

13 October 2016

Dave Smallshire is a dragonfly recorder for Devon and former trustee of the British Dragonfly Society. He began his talk by showing us pictures of the oldest dragonfly fossils of 350 million years ago, still easily recognisable today.

There are about 6000 species of dragonfly and damselfly globally and 48 species have bred in the UK. Devon provides a wide range of habitats including lowland rivers and streams, canals, ditches, lakes and ponds, and 29 species breed here.

The common name often indicates their method of feeding, with skimmers catching insects over water, and darters, hawkers or chasers. They use a large jaw which can shoot out to catch prey. Our largest dragonfly, the emperor, can catch butterflies on the wing, while small damselflies take aphid-sized prey.

From late spring onwards they emerge from the water where they will have spent usually one or two years passing through their larval stages. They need a good supply of invertebrate food and unpolluted water.

Emergence is often in the evening, when they climb up vegetation and rest while the abdomen and wings harden and their pigment gradually appears. This can take up to two hours in a large species and is the most vulnerable stage in their life cycle, when they can be damaged by the weather or attacked by ants.

The adults lay eggs directly in water or on nearby vegetation and can often be seen flying in tandem. Some hawkers lay their eggs inside plant stems. The adult stage of their life cycle is brief, a few weeks for damselflies and a few months for dragonflies, eventually killed by the cold and lack of food.

The fascinating talk was illustrated by Dave’s own beautiful photographs.

Mary Jenking CBiol MRSB

Seaton Jurassic Centre

2 July 2016

The Devon and Cornwall branch is lucky to have the Jurassic Coast, a natural World Heritage Site, on its doorstep. Mike Green gave us a clear and enthusiastic account of the geology of the site, illustrated with models and fossils characteristic of the various rock types.

The Heritage coast stretches from Exmouth eastward for 96 miles to Studland Bay near Bournemouth. It is the only place in the world that reveals the three epochs of the Mesozoic era, the Triassic from about 248 million years ago, Jurassic, from 200 million years ago and the Cretaceous, 144 to 65 million years ago. Sedimentary rocks are laid down horizontally of course, but from the tilting of the land they are now exposed progressively along the coast.

During the Triassic the area was a red sandy desert and this is seen in the west of the site, with high red cliffs, sandstone stacks and not many fossils. As the continents were separating from Pangea, sea levels rose and the Jurassic deposits formed in shallow seas. Here clays and shales predominate, high in calcium fixed by marine organisms. Amongst the fossils are gastropod molluscs, echinoderms, insects, fish and amphibians and plant material.

There is a fault line at Beer, Devon, and the two sides represent about 1 million years of change. In the Cretaceous period to the east the area had lowland swampy conditions, later overlain by chalk. Here fossilised reptiles (including dinosaurs) and mammals are present.

In the afternoon we enjoyed the Seaton Visitor Centre which deals not only with geology and fossils but provides interactive demonstrations of world environmental issues.

Brian Wood FRSB

Royal Title Celebration at the Eden Project

30 April 2016

I saw a birthday card recently which claimed that a party without a cake is just a meeting. Devon & Cornwall’s recent event at the Eden Project was definitely a party, as a celebratory cake was cut and consumed before guest speaker Christopher Bailes presented his fascinating talk about the Chelsea Physic Garden - connecting people with plants for three centuries.

Christopher was curator at the RHS Rosemoor Garden from 1988 before moving to the physic garden as curator in 2011. We heard that the garden has undergone many changes over the years, with little remaining from the original Apothecaries Garden that was created in 1673.

All gardens evolve – they develop and are interpreted in different ways by successive generations – and the Chelsea Physic Garden is essentially a botanic garden with a mission to demonstrate the medicinal, economic, cultural and environmental importance of plants to the survival and well-being of humankind. I think Hans Sloane (who donated the land for the original garden) would approve.

After lunch, Eden Project horticulturist Ian Martin spoke about his background and the role that the centre plays in connecting people with nature, before guiding the group around the Rainforest Biome.

Ian has an illustrious 20 year history at the Eden Project – he was plant nursery curator for 15 years and is now technical advisor. His enthusiasm for the specimens planted in the biome is exceeded only by his desire to ensure that all visitors learn about the importance of their conservation and the protection of their natural habitats.

During our tour we were treated to a presentation about Amorphophallus titanum – the Corpse Flower – three of which were close to flowering, when they emit their eponymous stench.

Our thanks to Christopher Bailes and Ian Martin for making this a celebration to remember.

Dr Ian M Varndell CBiol FRSB

Winter Birds and Seals Boat Trip

17 January 2016

Devon and Cornwall RSB members joined the weekly Sunday morning bird-watching trip from Paignton harbour, around the coastal cliffs, out to sea, then onwards to Brixham harbour and back again. We were in the excellent hands of naturalist Nigel Smallbones and the crew of the Dart Princess.

The weather was crisp, cold, bright and clear. Good for wintering birds and also to allow clear views and explanations of the geology of the cliffs, including limestone and striated layers of sandstone.

Leaving Paignton harbour we were immediately dive-bombed by a male Peregrine. On the trip we had frequent close sightings of many birds including 17 Great Northern Divers, 18 Great Crested Grebe and Scoters in flight. There were 900 plus Guillemots on the colony cliffs at Berry Head and many more in the water in the Brixham area. Seals were also basking in the cool sunshine in Brixham harbour.

Interestingly, despite the northerly movement of many auks associated with climate change, the Guillemot colony here on the South Devon coast is increasing steadily in numbers year by year.

A good trip and as we got back into Paignton harbour we saw both the male and female Peregrines, just before the rain started!

Mr Michael Morgan MRSB

Science and Nonsense in Drug & Alcohol Policies

19 November 2015

By his own admission Professor David Nutt polarises opinions. During an entertaining, thought-provoking and informative lecture delivered to a packed audience of over 300 people at the University of Exeter, Professor Nutt provided evidence of complicity, media mis-rapportage and ignorance underpinning the Government's position that "illegal" drugs are dangerous and cannot be used under any circumstances, including in clinical research.

By his own admission Professor David Nutt polarises opinions. During an entertaining, thought-provoking and informative lecture delivered to a packed audience of over 300 people at the University of Exeter, Professor Nutt provided evidence of complicity, media mis-rapportage and ignorance underpinning the Government's position that "illegal" drugs are dangerous and cannot be used under any circumstances, including in clinical research.

Sacked in 2009 from his post as Chair of the Advisory Committee on the Misuse of Drugs by Labour Home Secretary Alan Johnson, Nutt has been an outspoken advocate for evidence-based drugs policy, rather than the seemingly irrational approach taken by successive administrations.

Nutt presented compelling data on the accelerating incidence of liver disease, clearly illustrating that alcohol is the most dangerous drug. It affects the individual who consumes it, those close to those who abuse it, as well as society in general which has to suffer the impacts of its consumption.

Conversely, he showed the vilification of MDMA ('ecstacy', or 'empathy' as it was first named) by the mass media, and presented evidence of miscommunication in cases where 'mephedrone', formerly a 'legal high' was 'confused' with methadone (a heroin substitute) to exaggerate its danger to society.

Nutt's research is focused on researching the clinical utility of 'illegal' drugs – psilocybin (from 'magic' mushrooms) as a treatment for depression and cluster headaches, and MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder. Gaining access to these drugs for clinical research can take years, and is set to get worse.

The Psychoactive Substances Bill, which is likely to gain Royal Assent in 2016, will ban the sale of psychoactive substances regardless of harm and benefit (including nitrous oxide which is widely used for pain relief), and could end essential research work and needlessly delay new therapeutic drug development. Is this the worst moral law for more than 400 years?

Watch the talk in full on the Exeter University website.

Dr Ian M Varndell CBiol FRSB

Micrographia

24 October 2015

In 1665 Robert Hooke published Micrographia, the first fully illustrated book on microscopy – a whole new world of tiny things. To celebrate the 350th anniversary of the book and its beautiful illustrations, Exeter Cathedral hosted our day of microscopy and drawing, in the Chapter House.

The book was presented in a glass case so that we could see the detail of the drawings and text. Ellie Jones, the Cathedral Archivist, was in attendance to explain its importance and how it was being conserved.

Exeter University provided modern microscopes and slides, giving everyone the chance to compare what we can see today with the tiny images that Hooke saw. Dr Charlotte Walker and Dr Emma Rundle from the Marine Biological Association provided an antique microscope and information about the history of microscopy in marine research.

During the day Professor Gero Steinberg from Exeter University gave a lecture on the development of microscopes up to the present day and Dr Felicity Henderson from the English Dept of the University gave a talk on Hooke and Micrographia.

The event was linked to the Big Draw, a national celebration of drawing that takes place annually in October. Visitors of all ages attempted to draw their own versions of tiny insects and plants and marvelled at the skill of Robert Hooke.

It was a delight to receive so many appreciative comments from members of the public who had never looked down a microscope before – much better than just seeing it on television was one response.

We should like to thank Exeter Cathedral, Exeter University and the Marine Biological Association for their help and enthusiasm.

Mary Jenking MRSB

Visit to Upcott Grange

27 August 2015

"The large copper butterfly is really dependent on beavers". That got our attention as we were welcomed to Upcott Grange by Derek Gow, whose consultancy is dedicated to reversing the decline in water vole populations.

Derek's work involves breeding and releasing voles into habitats where suitable riparian conditions have been recreated and the North American mink has been eradicated. Micro-chipping the voles allows recapture surveys to identify any wild-bred progeny. His re-introductions have been successful in various sites around the UK.

Derek also has beavers at Upcott, and we waited by their enclosure as the sun went down, hoping to catch sight of them. Though only August, the chilly air sent us back indoors without a glimpse.

We were compensated by seeing some of the many Upcott water voles close up. Here's a tip: the most essential piece of equipment for catching your vole is a Pringles carton – exactly the right size for a chubby little vole to scuttle into.

We left feeling that there is hope for this little British native again. What they need most is open, sunny wetlands with lots of banks and vegetation, something they are likely to get here where the newly discovered wild beavers quietly remodel the River Otter.

A helping hand from one native Briton for a distant mammalian cousin – and hopefully for the large copper butterfly too.

Dr Alma Swan FRSB

Biology Week lecture: The Improbable Origin of Life

14 October 2014

Dr Nick Lane from University College London spoke to an enthusiastic audience of about 250 people on 'The Origin of Life'.

What are the chances that intelligent life might have evolved elsewhere in the universe? Nick favoured the Jacques Monod/Stephen Jay Gould school of thought that all was due to chance events – that even if there were intelligence elsewhere, distance and time would work against finding it.

It was evolution in the eukaryotes that led to the great structural and ecological complexities culminating in intelligence. The characteristics that define them include include a nucleus with mitosis and meiosis, speciation and senescence. Recent studies indicate that another key characteristic is chemiosmosis (the movement of ions across a selectively permeable membrane), the presence of mitochondria playing a key role in this.

The case was made that complex life arose only once in four billion years through a chance combination that 'worked' positively and accounted for all the special characteristics of the Eukaryota. No prokaryotes had developed any of these characteristics in that time.

There followed a lot of questions and comments with which Nick dealt easily, offering helpful technical clarification. His new book, The Vital Question is due out in February 2015. If it is of equal quality to that of his talk, it promises to be a good read.

Chris Fry MSB

AGM and nanoscience talk

12 March 2014

The speaker at our AGM at the University of Plymouth was Professor Richard Handy, director of the Exotoxicology Research and Innovation Centre at the university. The centre has a strong interest in nanoscience and works on many different organisms, from microbes to man.

At less than 100nm nanoparticles are little wider than the DNA helix. Early examples were made for cosmetics, fabric coatings and fuel additives. By 2011 there were over 1,300 products on the market and the industry was worth around $1,500bn. The particles are mainly carbon, silver and titanium-based and produced chiefly in the US and Europe.

Around 50 have been approved as medicines so far, including drugs for cancer and pain control. Nano-silver is being investigated for antibacterial properties in dentistry, while nano-iron may prove useful in breaking down persistent pesticides. There is interest in the optical properties of certain particles which change colour according to their size.

Exotoxicity is being studied in algae, crustacean and mussels, but very little is known about the effects of nanoparticles in amphibians, reptiles and birds. Studies are comparing the effects of nanoparticles with those of dust, ash and carbon particles on human respiratory epithelium. There are also some concerns about nanoparticles aggregating in coastal sediments and thereby entering food chains.

In a fascinating and wide-ranging talk Professor Handy explained that nanoparticles can potentially deliver huge benefits, but there are many gaps in our knowledge of the risks to ourselves and the environment.

Mary Jenking CBiol MSB

Can Insects Feed the World?

17 Jan 2014

Dr Peter Smithers (Plymouth University) entertained an audience of almost 70 with a talk on entomophagy – the consumption of insects.

Over 2 billion of the world's population already includes insects as part of its diet, and Dr Smithers is an enthusiastic advocate of insects as a high protein substitute for quadruped meat.

The production economics are compelling. To generate an equivalent amount of protein, insects require one-tenth the land, one-sixth the feed, and one-tenth the maturation time than cattle – plus they release far less CO2 than cattle. But can insects form more than a novelty addition to diets in 'developed' countries? A few companies in the UK are distributing insects for culinary use, but prices are high and products such as silkworm pupae have not yet made it to supermarket shelves.

After the talk, the Society's in-house crooner (and regional coordinator) David Urry brilliantly encouraged us in song to "stuff insects down our throats"...which we duly did. Devon-based Master chef Peter Gorton cooked a delicious cricket risotto followed by brownies covered with caramelised mealworms. The fact that several attendees went back for seconds shows that insects could become staple ingredients in our diets. Perhaps in the near future one of your "Five a Day" might be selected from grasshoppers, giant water bugs and sago worm larvae?

Mary Jenking CBiol MSB

Umberleigh Farm Visit

5 October 2013

Trevor Wilson FSB invited members for a tour of his farmland in Umberleigh. Two of his Exmoor ponies were waiting to meet us. One of the world's oldest breeds, the Exmoor ponies are the most primitive of the North European equines, with genetics distinct from other horses. Currently there are about 2200, but only about 160 foals are born a year so they are classified as endangered.

Ron Smith introduced us to his Devon Closewool sheep. They are known for their dense medium length fleece, ideal for survival in wet, cold conditions and for producing full-flavoured, succulent meat. They are at risk because they are only found in a small area, making them more vulnerable to disease.

After this introduction to two rare breeds we boarded a trailer, sitting on hay bales for a tractor tour of the Pouncey family's farm. We learnt about various aspects of health and welfare including traceable ear tags. An animal passport has to be with each animal on every movement throughout its life. This is essential for monitoring the spread of disease.

After a superb lunch by Atherington and Umberleigh WI, Trevor gave a talk about the diversity of livestock breeds in Devon. Some such as the Red Devon cattle have been exported all over the world including America, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil and Russia.

There are probably about 3200 tigers left in the world. None of our rare livestock breeds have that number.

The survival of our rare breed livestock now remains in the hands of individual farmers and Rare Breed Societies.

Mary Jenkins CBiol MSB

Spinal Frolics

3 September 2013

Consultant spinal surgeon Mr Andrew Clark alerted us to the personal journey our spines undergo during a lifetime and what happens when things go wrong.

This lecture was attended by an eclectic range of membership, age and profession, some of whom made full use of question time, obtaining a personal medical consultation!

The talk was hugely enjoyed by all; a GP loved being reminded of student days, a former school teacher was fondly reminiscent of anatomy classes, and a young County Cricket fast bowler who had spent 6 months training in the New Zealand Cricket Academy was relieved and grateful to receive information about potential sports injuries. Many found it informative and illuminating, all the more so for a young practising osteopath, eager to earn CPD points.

Our chair Mary Jenking, presented a Society of Biology Long Service Certificate to former chairman and treasurer Brian Petts. We celebrated with a finger buffet and delighted in meeting old friends and making new ones.

Our thanks to Mr Andrew Clark and staff, and Mr Christopher Weatherley the Founder and former director of the Spinal Unit.

Chris Fry MSB

Victorian Plant Hunters & Pioneers

27 April 2013

Plant historian Caradoc Doy entertained members and their guests at Exeter University with the fascinating story of the Veitch Nurseries of Exeter and Chelsea. Caradoc gave a detailed overview of the firm, illustrated with slides of the many popular plants they introduced. These nurseries sent out 23 collectors over a period of 72 years, and were responsible for many horticultural firsts including sending out collectors around the world to collect hundreds of new exotic plants.

In 1840, William Lobb, travelled to South and North America, bringing back the monkey puzzle, (Araucaria), fuchsias, escallonias, Caenothus, Embothrium, Lapageria, Crinodendron, and later many conifers, most famously the Wellingtonia. On one dangerous journey he obtained Araucaria araucana cones by rifle shot! The seedlings were later sold for about £300 each (current value).

In 1854, John Dominy, the chief hybridiser was credited with raising the world's first official orchid hybrid, Calanthe x Dominii. This led to the establishment of a new branch of horticulture which was controversy in Victorian Britain and was regarded as 'tampering with nature'.

We enjoyed our exploration of the university grounds and found specimens planted by the Veitch's over 100 years ago. The exuberance and enthusiasm of the speaker was much appreciated. A limited edition of the centenary reprint of Hortus Veitchii can be obtained from www.caradocdoy.co.uk

Christine Fry MSB

Getting up close and personal

19 October 2012

An eclectic mix of about 40 members attended – students, oldies and those who have not been in contact for a while. We last visited the zoo in 2000 and much had changed.

An eclectic mix of about 40 members attended – students, oldies and those who have not been in contact for a while. We last visited the zoo in 2000 and much had changed.

Dr Amy Plowman, head of field conservation and research, introduced us to the scientific work of the Zoo and Trust. In small groups, members of the science team led us round the zoo, highlighting key species in their research. The higher primates provided interesting insight into group dynamics. A hot buffet lunch followed in a highly convivial atmosphere, with members exchanging ideas and discoveries, and catching up with each other's news.

Sated with delicious food, we were put into interest groups, experiencing exclusive behind the scenes visits to chosen areas - Avian Breeding Centre, Bio-secure Amphibian Breeding Unit, and Giraffe Quarters. We loved feeding giraffes, (and visiting in threes on tip toe, the recently born giraffe baby). Some chose to visit the state of the art greenhouses accommodating vertical hydroponic growing systems, (Verticrop) - the produce of which formed part of our lunch.

A splendid visit much enjoyed. The staff was especially generous with their time, enthusiasm and expertise. Many of us wandered around the zoo afterwards until it closed.