RSB@10: The first decade & beyond

The Society of Biology, now the Royal Society of Biology, was founded 10 years ago this month. The Biologist convened a panel of key figures in the Society’s history to discuss why a unified voice for the biosciences was needed, what the organisation has achieved in its first decade and how it should change to support the biosciences of the future

The Biologist 66(5) p20-23

Throughout the 20th century and into the early 2000s the views, needs and interests of the life sciences were represented to government by as many as 80 learned societies and membership organisations. The Biosciences Federation was formed in 2002 to try to unite life science organisations over issues of common interest, but there was still overlap between it and the work of the Institute of Biology, which had been representing individual biologists in the UK since the 1950s.

In 2009 a merger between the two organisations led to the creation of the Society of Biology, which aimed to provide a unified voice for life science in the UK. Dame Nancy Rothwell was instrumental in bringing the two organisations together, at first via an exploratory working group and later as the Society’s first president.

The Society was awarded a royal title in 2015, becoming the Royal Society of Biology (RSB), and now boasts more than 18,000 individual members and almost 100 Member Organisations.

To celebrate the past 10 years The Biologist held a roundtable discussion to reflect on the formation, development and future of the Society. Our thanks to those who took part.

Dr Aileen Allsop FRSB Current Fellowship Committee member and RSB Council member, 2009–2016

Kenneth Allen FRSB Branch co-ordinator at the Institute of Biology and interim chief executive of the Society of Biology in 2009

Professor Nigel Brown OBE CBiol FRSB Current chair of the RSB’s College of Individual Members

Professor David Coates MBE FRSB Founding honorary secretary and current chair of the RSB Accreditation Committee

Professor John Coggins FRSB Former treasurer of the Biosciences Federation and chair of the RSB College of Organisational Members, 2009–2018

Professor Sir Peter Downes OBE FRSB RSB Council member, 2009–2017

Dr Mark Downs CBiol FRSB RSB Chief executive since 2009

Dr Pat Goodwin CBiol FRSB Former honorary treasurer of the RSB

Professor Christopher Kirk FRSB Former honorary secretary of the RSB

Dr Elizabeth Lakin FRSB Former chair of the RSB Accreditation Committee, RSB Council member, 2009–2016

Professor Hilary MacQueen CSciTeach FRSB Current RSB Council member, former chair of the Heads of University Bioscience

Professor Richard Reece CBiol FRSB Current honorary secretary and chair of the Society’s Membership and Professional Affairs Committee

Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell CBiol Hon FRSB Former president of the Biosciences Federation and founding President of the RSB

Professor Claire Wathes FRSB Current member of RSB Council and the Society’s Audit Committee.

The panel on...The need for a ‘unified voice’ for biology in 2009

John Coggins: At that time EU regulations were being developed about animal experimentation and the biology community was not getting to grips with advising the government what to do. I can remember vividly going to various meetings when Lord Sainsbury was the science minister and seeing him get quite angry that the life sciences didn’t have a focused lobby.

David Coates: There were so many life science organisations, all saying different things – chemistry had gone through similar evolution many years before. I remember meeting with an MP about how to make representations to government. He said: “You write a four-page document with the summary at the front, not a 30-page document with a summary at the back.” And the problem was every single life science organisation was doing just that. We had to bring it together somehow.

Christopher Kirk: UK science had also entered a time when it was clear funding would be under huge pressure. What was paramount in everyone’s mind was how to respond to those funding problems.

Pat Goodwin: Nancy [Rothwell] proposed I sit on this interim council of both organisations, and I remember she wanted an answer in five minutes – which was quite difficult as I was in Malawi. It wouldn’t have happened without Nancy.

Kenneth Allen: I vividly remember I was driving down the M40 in a blizzard one day and David Coates called me. He said: “We’re going to merge with the Bioscience Federation, would you become the interim chief executive?”

Nancy Rothwell: I was on the first Council of the Biosciences Federation, formed after much debate and a very hard push from [then science minister] Lord Sainsbury that biology was too dispersed, with far too many different societies, to have impact. We realised that there wasn’t room for two organisations, as there was too much overlap, and huge potential impact and efficiencies to be gained from merger. So, after a great deal of very hard work, the Society of Biology was formed.

Science minister Chris Skidmore speaks at the latest Parliamentary Links Day, organised by the RSB.

Science minister Chris Skidmore speaks at the latest Parliamentary Links Day, organised by the RSB. On how bioscience is changing...

Nancy Rothwell: Life sciences has become less descriptive and more mechanism driven,

less disciplinary-focused and more integrated between disciplines, both within life sciences and with other fields.

Peter Downes: There’s a lot more scale now. Biology is just a bigger subject with bigger infrastructure requirements, all of which requires us to have a co-ordinated ability to develop policy for those needs in comparison with areas such as physics and chemistry.

Most of the big questions in biology now require you to work in more than one discipline, either as interdisciplinary teams or groups or in leadership. It’s the same in industry – there is no way you can answer new questions on, for example, drug discovery just with teams of biochemists.

We’ve heard about the disappearance of discipline names and departments – that’s not come to the completely logical outcome yet. I think we will name biology groupings after the question they are answering, not the discipline that serves them, because there will undoubtedly be multiple disciplines serving these big, complex questions.

Richard Reece: Now, and into the future, the skill of the biologist is interpreting recommendations from the data analysis to make sure it is relevant in a biological context and that it makes sense.

Pat Goodwin: I think something that is beyond science is the way people’s careers will change. There will be more people working part-time, or doing four-day weeks, plus more maternity and paternity leave. That is bound to have an effect on research, as well as efforts to improve diversity and inclusion. The Society has a role to play there.

Aileen Allsop: I think there’s a push from younger people that they want a different definition of work-life balance compared with the one that we grew up with.

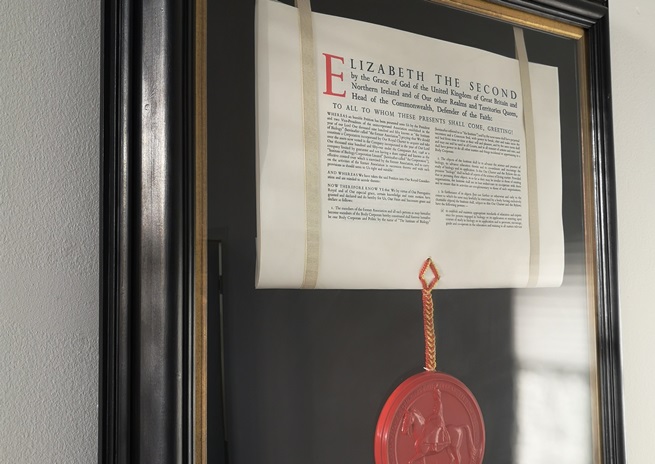

Forty years ago, the Society's predecessor organisation the Institute of Biology was granted a Royal Charter to represent the UK's biologists. The Society formed in 2009 and was awarded a Royal Title in 2015. The charter now hangs in the RSB's new offices in central London .

Forty years ago, the Society's predecessor organisation the Institute of Biology was granted a Royal Charter to represent the UK's biologists. The Society formed in 2009 and was awarded a Royal Title in 2015. The charter now hangs in the RSB's new offices in central London .On the highlights of the past decade...

Richard Reece: Being awarded the royal title has been a significant advance for the Society and has made an absolutely huge difference, especially when we’re doing accreditation overseas.

Accreditation of bioscience degrees was something that a number of us had tried under the auspices of various member or predecessor organisations, and simply failed. That was something only the RSB could have done.

David Coates: Accreditation is making a huge difference to higher education and internationally.

We are the only (bioscience) organisation in the world that does it.

Christopher Kirk: A big success has been that we are now a place where government will actually come along and ask what the biology community thinks. That simply didn’t happen 10 years ago.

Nancy Rothwell: The fact that the Society has managed to integrate leading biologists, students, teachers and passionate ‘amateur biologists’ has been so important.

Pat Goodwin: The parliamentary work has been amazing and the young people have been enthused by it. That’s what we should be focusing on – getting the next generation into science policy and parliament.

Aileen Allsop: Animal research – the UK played a leading role in getting that sorted. Otherwise we would have had European legislation that was plain ridiculous.

Mark Downs: One of the highlights has to be Biology Week, which provides a clear focus for engagement with the biosciences and pulls together all of that activity really well.

Nigel Brown: I’m now hearing biology that I wouldn’t have sought out professionally through attending branch events, and it’s also what The Biologist does very well. That is a benefit of being engaged with the Society as a member.

RSB staff Raghav Selvam and Lucy Coia celebrate the Society's latest membership milestone

RSB staff Raghav Selvam and Lucy Coia celebrate the Society's latest membership milestoneOn areas for the RSB and learned societies to focus on in the future...

Aileen Allsop: Whether we like it or not, the B-thing [Brexit] is going to happen, and that will completely change the face of science in the UK. Nobody knows what is going to happen, so we need to provide some leadership there.

David Coates: We’re very focused on molecular sciences in the UK at the moment. With Brexit coming up, agriculture and the environment will be ever more important. The Society will have to be aware of where it is looking in terms of policy and education.

Richard Reece: The way we do research is very different – the barriers between disciplines are being eroded and there is a lot more mathematics, physics and chemistry in biology, and that really makes a difference to the way an overarching organisation can look after the people in those sectors – with that changing view of what their work is going to be.

Nigel Brown: You can be an amateur biologist when it is very difficult to be an amateur chemist.

That makes up a small percentage of our membership, but it is increasingly important with things like citizen science.

Claire Wathes: With schoolchildren striking over climate change at the moment I’d like to see the enthusiasm among young people for the environment and our activities – like branch events – brought together somehow. At the moment they seem very far apart. It is also absolutely vital that we engage with the public to provide accurate information, as it is so easy to find misinformation about biology now. We need somebody there to provide trusted facts.

Aileen Allsop: A lot of young people understand how they can live their lives in a way that helps the environment, but don’t understand the careers open to them that could help the environment too. We could have a role in that. If there aren’t too many jobs out there now, there will be in the future.

David Coates: We [the RSB Accreditation team] have set down a set of rules on what higher education in the biosciences should be like, but what we absolutely have to avoid is straightjacketing ourselves. There’s a real danger of building a tradition that doesn’t allow for change and flexibility. What I would want is for the Society to maintain the flexibility to recognise the change that’s going on around us. There’s always change and the job’s never finished.

Hilary MacQueen: There’s been some valuable work on diversity and inclusion, and returners to work, but the impact has not been as good as we would like. Increasing that work is necessary and we need to be at the front of that not trotting at the rear.

Peter Downs: Publishing, the primary source of income for the majority of learned societies, is about to go through a traumatic set of experiences around open access. The surest way to ensure learned societies’ publishing gets picked off is if each one acts in isolation, with limited resources for change and investment in a different future. The new model has to deliver an outcome where publishing costs the community less than it did before. How do we create greater integration in terms of the things that link us all?

Elizabeth Lakin: Yes, we’ve got to drive this forward so that if we were to do this again in 10 years’ time, we would have a better balance in terms of the diversity and backgrounds round this table.

• The Biosciences Federation was formed in 2002 with the aim of uniting the bioscience organisations over issues of common interest related to research, policy and teaching. By 2007 it had 51 membership organisations, from learned societies to pharmaceutical companies.