Focus on...Allergies

As the Society launches #BritainBreathing, an app to help researchers monitor the public's seasonal allergies, we look at the biology of allergic reactions

The Biologist 63(3) p32-33

The media are constantly searching for answers as to why more and more people seem to be experiencing allergic reactions. While many people can confuse allergies with food intolerances or other illnesses, allergies do seem to be rising at an astonishing rate in developed countries.

Seven times as many people were admitted to hospital with severe allergic reactions in Europe in 2015 than in 2005, and in the 20 years to 2012 there was a 615% increase in the rate of hospital admissions for anaphylaxis in the UK[1]. The percentage of children diagnosed with allergic rhinitis and eczema have both trebled over the last 30 years[1].

What is an allergy?

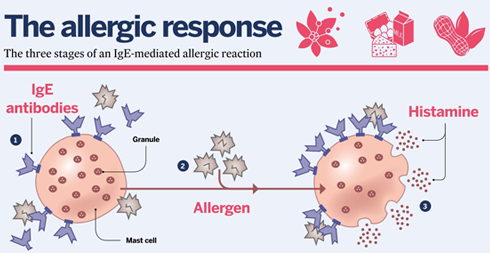

Allergies occur when the body treats a harmless substance as a threat and the immune system produces an unnecessary response to it. In biomedical terms, it is an inappropriate immune response to a particular protein, often involving immunoglobin E antibodies (IgE).

IgE-mediated allergic reactions are the most common and well understood, and cause conditions such as asthma, hay fever, allergic dermatitis and many food allergies. Non-IgE allergies, involving other antibodies, are rarer and more complex.

The first step of developing an IgE allergy is sensitisation: the immune system mistakenly produces IgE antibodies when it detects the presence of a certain protein. These antibodies bind to the surface of white blood cells called mast cells, leaving them 'sensitised' to the substance.

The next time the person comes across this allergen, mast cells with these specific antibodies attached release inflammatory substances, such as histamines and prostaglandin, which act on the surrounding tissues. Symptoms can be mild and localised to life threatening and affecting the entire body.

Cross-reactive allergies occur when a person is sensitive to one allergen, but another substance has proteins on its surface that are similar enough to trigger the same allergic response.

Why are allergies increasingly common?

The 'hygiene hypothesis' has been around since the late 1980s, and suggests that exposure to bacteria and other substances reduces a child's risk of developing allergies. It is thought that as our living conditions have improved, this exposure has been reduced, and this could in some way be influencing how our immune systems behave.

In a similar vein, the 'old friends mechanism' suggests that exposure to bacteria helps form a healthy microbiome (gut flora), which in turn helps us to develop a well-functioning immune system.

A recent review of 'the allergy epidemics'[2] of the past century concludes that improved hygiene has almost certainly played a role in the increasing rate of allergies in the developed world, but there are other factors involved, from how much time we spend indoors to a lack of exercise. More recently, advice to avoid feeding babies and young children allergy-causing foods is also thought to have actually made the development of allergies more likely[3].

1. IgE antibodies are produced by plasma cells in response to the presence of an allergen. The antibodies attach themselves to mast cells.

2. On subsequent exposure, the IgE antibodies on these mast cells bind to the allergen.

3. IgE-primed mast cells release histamines and other chemicals (degranulation), leading to allergy symptoms.

What else is there still to find out?

The intricacies of individual allergies are still not well understood. Sensitisation can occur any time in life, but it's not clear what triggers the initial response; not all sensitised people will go on to develop an allergy; the same type of allergy can cause different symptoms in different people; an allergy can cause wildly different symptoms in a person each time it occurs; and allergies can also come and go. People can be genetically predisposed to allergies, but this doesn't help us predict exactly who will develop an allergy.

Pioneering studies such as the LEAP project (see below) suggest how we are first exposed to a substance is important, but there is still much to find out. Further, some allergies are better studied than others.

Can allergies be treated?

Traditionally, people with allergies have had to avoid the allergen that causes their symptoms, or treat the symptoms once they suffer a reaction. But findings from an Israeli study known as LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy)[3] may help us prevent people developing allergies.

LEAP has found that Israeli children, who are exposed to peanuts early in life through diet, are less likely to develop peanut allergies. It goes against years and years of government advice in the UK to avoid peanuts, which may have in fact contributed to the rise in peanut allergies.

An even more exciting goal is to be able to 'cure' people of their existing allergies. Immunotherapy, which involves exposing people to their allergen in minute doses, is starting to show promise after being dogged by poor practice throughout the 1970s.

The mysterious appearance of new allergies, and the tendency for people to mistakenly self-diagnose them, has led the media to "almost trivialise them", says Dr Louisa James, an allergy researcher from King's College London. She hopes more awareness and research can ultimately reverse the trend and eventually overcome allergic reactions altogether.

"Allergies can have a huge impact on quality of life. It is important to bust myths as allergy is very serious," she says.

BritainBreathing, the Society's new citizen science allergy project developed with The University of Manchester and the British Society for Immunology, can be found at britainbreathing.org

References

1) Making Sense of Allergies, Sense about Science, 2015.2) Platt-Mills, T.A.E. The allergy epidemics: 1870–2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol 136, 3–13 (2015).

3) www.leapstudy.co.uk