No time to waste

International environmental goals and dedicated sustainability teams are needed to reduce the impact of bioscience on the organisms and ecosystems we study, writes Marta Rodríguez-Martínez

February 21st 2022

In the last few decades the speed of scientific and technological development has made many believe in the illusion of eternal growth without consequences. Many of us forget, or choose to ignore, the high price our planet has to pay for such a growth model. We consume natural resources and pollute our environment like we have somewhere else to go when we exhaust what our planet can offer. This age of consumerism without conscience has spread into the vast majority of personal and professional domains, including life science research.

There are two main areas of concern when looking at the environmental impact of life science research[1]. The first is the CO₂ emissions associated with research activity, including travelling for work, conferences or other scientific gatherings – which in fact can be applied to all scientific disciplines[2,3]. Life science laboratories are particularly energy intensive: with ultra-low temperature freezers, complex ventilation, daily washing and autoclaving and high-energy beamlines, the carbon footprint of this research is significant. The footprint of a single researcher can be equivalent to several times that of an average individual and mean thousands of tonnes of carbon are released into the atmosphere per year at an institution-wide level.

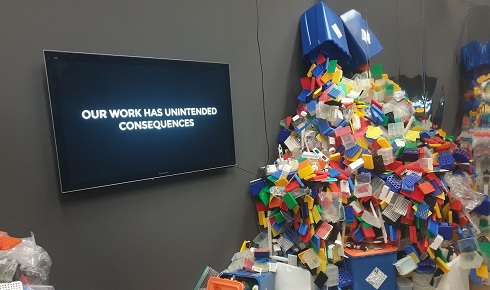

The second area of concern is the high volume of waste generated in the laboratory. The routine and vast use of single-use plastics is a key problem for the life sciences: an article from 2015 estimates that plastic waste from this discipline accounts for nearly 2% of the global total[4] – a shocking figure given that researchers of all disciplines only account for 0.1% of the population[5]. One team of researchers extrapolating their department’s plastic waste across the 20,500 institutions involved in biological, medical or agricultural research worldwide suggested that the plastic waste generated in 2014 alone could weigh as much as 67 cruise ships.

Life science is driven by a passion to understand and care about nature, and to see the positive impact our research has on the world around us. When you consider that our carbon emissions are contributing to the climate crises we so desperately want to prevent, and that our plastic waste and microplastics are entering the ecosystems that we study and preserve, it is clear that life science research needs to undertake a fundamental change – and there is no time to lose.

Life science researchers must implement fundamental changes to processes if they are to lower their carbon footprint and reduce their plastic waste. The display of plastic waste is from the 'Paradox of Science' exhibit at the Museum De Lakenhal (by DREAM3D lab / Princess Máxima Center).

Life science researchers must implement fundamental changes to processes if they are to lower their carbon footprint and reduce their plastic waste. The display of plastic waste is from the 'Paradox of Science' exhibit at the Museum De Lakenhal (by DREAM3D lab / Princess Máxima Center).A search for standards

Just as in every other sector – and perhaps more so – the life science sector needs to start implementing sustainability standards. This cannot be done with a traditional top-down model: fundamental changes require input and collaboration from scientists themselves to ensure these changes do not have a negative impact on research quality, and are accepted and implemented globally.

Implementation needs to be done with a two-way, combined approach[1]. Benchmarks and standards are set bottom-up based on the input and advice of researchers, but their implementation can’t only rely on the goodwill of scientists – they need to be governmentally or institutionally regulated (top-down). At the moment only a small part of the scientific community is developing sustainability projects and policies, and any new system must stress the importance of all in the sector complying with these regulations, including equipment suppliers and funding bodies.

Some research institutions have already adopted models and measures around sustainability, combining expertise from their scientists and from sustainability professionals. For example, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Europe’s only intergovernmental organisation for life science research, with more than 110 independent research groups across six cities, recently made its first sustainability strategy public. The organisation has committed, by 2030, to eliminate the use of non-essential single-use plastic, reduce total waste by 20%, reduce energy-based and travel-based emissions by half, and recycle 90% of its waste.

A full-time problem

Although the importance of expertise in research sustainability is certainly acknowledged within scientific institutions, there remains a belief that scientists should dedicate their free time to the cause. Many sustainability projects rely on the voluntary efforts of a particularly ‘green group’ of scientists, without the involvement or collaboration of the directorate.

The most efficient and fair way of dealing with sustainability in research would be the combination of both sustainability and research professionals. Unfortunately, in most cases across Europe sustainability in research centres is not close to this model and is driven only by scientists in a purely bottom-up approach. It is the scientists themselves asking for a paradigm change and for the creation and implementation of sustainability standards.

Despite this, the goodwill and passion of scientists, many of whom have become expert advisers beyond their paid roles, has in some cases reached beyond their own labs and research centres, creating several impressive initiatives to promote sustainable research practices on a wider scale. Some of these are national (for example, Green Labs Austria and Green Labs Netherlands), some are clustered by discipline or frameworks to promote exchange of knowledge (Labconscious and www.greenyourlab.org), and some are cultural events to make the public aware of sustainability issues (for example, ‘The Paradox of Science’ exhibition at Museum De Lakenhal, Netherlands).

There have also been high-profile scientific articles on sustainability in science[4] and many visible efforts to organise scientific meetings in a more sustainable way[2,6]. In all cases the level of involvement and work of scientists in this cause is commendable. Unfortunately, not all researchers have the resources and support necessary to participate in or drive these initiatives, nor should the responsibility rest on their shoulders alone. Life science researchers tend in many cases to underestimate the environmental impact of their activity and overestimate the effort of making changes to be more sustainable. In the same way, there is a predisposition to believe that more sustainable means less efficient or more expensive, when in reality in most cases it is the opposite.

A central framework

This exposes the need for central information, coordination and support for the existing initiatives as well as the promotion of new ones. Even though we need scientists to conduct their research in a more sustainable way and to provide input for sustainability benchmarks, it should not be their sole responsibility to do so, and policymakers and governmental bodies need to act now too.

Due to the lack of action from the very top, most sustainable initiatives and sustainable research programmes are initiated and run from the research institutions themselves, including efficiency assessment programmes such as LEAF. Although this demonstrates the drive and strength of the movement, we cannot rely on these initiatives alone to make global changes, and need to look for a way to put pressure on the policymakers and funders to establish certain standards in research sustainability.

It is clear that a central organised framework is crucial to generate the necessary research, data and reports that can influence policymakers, funding bodies and suppliers. Scientists and sustainability professionals have launched the Sustainable European Laboratories Network (SELs) to unite sustainable research initiatives across Europe, to provide high-quality reporting and research on sustainability in the life sciences, and the use of these findings to influence policymaking, funding bodies and manufacturer action.

It is hoped those embarking on local sustainability initiatives will find in SELs a central framework to help them succeed and find partners in their geographical area and research discipline. By providing a central platform for data reporting and training, SELs may also help develop the long-awaited European benchmarks for research sustainability.

When we look at the increasing number of sustainability initiatives in life science research, it is clear that most scientists are eager to conduct their research in a more sustainable way. They just need the resources, the information and the help of policies and regulations to prompt change. Change is clearly around the corner. Whether we choose to be the ones driving this change or wait to jump on the wave is up to us. As scientists we should know that the former is the most efficient. In the meantime, we have to keep encouraging the creation of new initiatives and the exchange of knowledge about research sustainability, and work together to achieve a more sustainable life sciences research model.

Marta Rodríguez-Martínez is a research scientist at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

1) Rodríguez-Martínez, M. Environmentally sustainable research is the only way forward. FEBS Viewpoints, 9 September 2020.

2) Holden, M. H. et al. Academic conferences urgently need environmental policies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1211–1212 (2017).

3) François Cluzel et al. Reflecting on the environmental impact of research activities: an exploratory study. Procedia CIRP 90, 754–758 (2020).

4) Urbina, M. et al. Labs should cut plastic waste too. Nature 528, 479 (2015).

5) Facts and figures: human resources. From the UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030.

6) Sarabipour, S. et al. Changing scientific meetings for the better. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 296–300 (2021).