Very cold and very old

5th December 2025

Tom Ireland talks to Greenland shark expert Professor John Fleng Steffensen about the world’s longest-living vertebrates – and how their maximum lifespan could be far longer than the current estimate of 300–400 years

The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is one of the world’s most fascinating vertebrates. With fearsome ‘cookie-cutter’ jaws at the head of up to a tonne of toxic, urea-soaked flesh, they live deep in the icy waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic, often accompanied by long copepod parasites that hang from their eyeballs. And while it had been suspected that these massive, cold-loving sharks could live for a very long time, a Science paper¹ by a group of Scandinavian and Greenlandic scientists in 2016 estimated that these elusive creatures might be able to live for a staggering 300 to 400 years. The world marvelled at the idea that some mottled old creatures in the ocean today may have been drifting through the deep since the time of Shakespeare and Galileo (the 17th century).

Central to the paper on the shark’s longevity was Professor John Fleng Steffensen, a biologist at the University of Copenhagen who has been studying fish in Greenland's icy waters since the 1990s. He began his research career as a comparative biologist, studying animals at the most extreme ends of the metabolic spectrum, such as shrews and elephants. In search of more interesting species, Steffensen travelled to the Amazon to study hummingbirds, to Australia to find lungfish and to Greenland to study the region’s small cold-adapted fish, which live in water temperatures that can be as low as -1.8°C.

“We were up in the north-western part of Greenland in a fjord system called Uummannaq,” he says. “We met a hunter in this simple skiff, with this 4m-long shark hauled onto the side of the boat. It was pretty much the size of the boat. And I said to the captain: ‘Bloody hell, that’s a Greenland shark!’ I was excited, but the captain was laughing. He said it was easy to catch them.”

When the locals told Steffensen that they believed the sharks grew very, very old, his eyes widened even more. “I’ve still never figured out how they knew this,” he says.

To local fishermen and indigenous hunters, the sharks are little more than an annoyance. Their meat is toxic to eat without extensive processing, due to high levels of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and urea. (While many sharks have high levels of urea to help maintain osmotic balance in saltwater, TMAO is believed to help stabilise proteins at extremes of pressure and cold.) When sled dogs or people eat the shark’s flesh as a last resort, they experience an unpleasant form of poisoning known as being ‘shark drunk’. The sharks were once fished by hunters for their liver oil and to help reduce the natural predators of the Greenland halibut, a major source of food in the region. Some figures suggest that tens of thousands were caught every year between the mid-19th century and the Second World War.

How old is old?

After his encounter with the giant beast in Uummannaq, Steffensen decided to explore the idea that they may live for a very long time. Sharks, like all fish, grow continuously during their lives, so their size is closely correlated with their age. Initially, the only data available on Greenland sharks came from a study that began in 1936, when over 400 individuals were caught, measured and released. Over the following 30 years just three were caught and re-measured reliably. The results, published in the 1960s, were fascinating nonetheless.

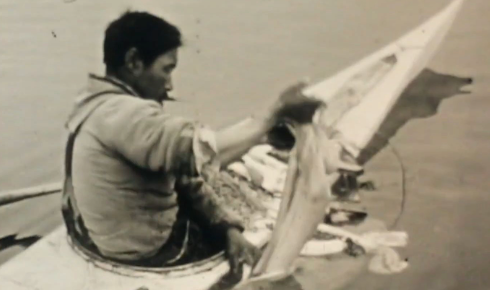

A local fisherman catches a Greenland shark in a kayak.

A local fisherman catches a Greenland shark in a kayak.

“One had grown one centimetre a year for eight years, another had grown half a centimetre a year for 16 years,” he says. For a shark known to reach 5m and beyond, such slow growth pointed to an animal that was living for a ridiculously long time.

This would be the beginning of Steffensen’s long obsession with determining the age of Greenland sharks. He and his colleagues’ research for the 2016 Science paper eventually used radiocarbon dating of crystalline proteins in the eye lens to estimate the ages of 28 female Greenland sharks. The paper made news headlines all over the world, and the idea that the sharks live to over 400 years old is now stated as fact almost every day in popular science articles, videos and social media posts.

Steffensen has lots to say about the ‘400 years’ figure and the true longevity of the Greenland shark. “First, we have never said they were 400 years old – we just said at least 272 years,” he explains (referring to the the low end of the estimated age range of the largest individual, which was 392 years ± 120 years). “When the Science paper came out we were not allowed to review the cover of the magazine or rewrite the ‘400 years’ headline on it.”

He now believes the data from that famous study might, at the same time, be both overestimating and underestimating the sharks’ ages. For a start, it is now believed that Greenland sharks may be pregnant for at least nine years, and possibly even longer. The radiocarbon dating was based on the assumption that newborn sharks’ lenses were zero years old, when in fact the lens proteins are formed in the womb many years before the sharks are born. Adjusting the growth curves for this long gestation makes the estimated ages of the sharks in the study a little younger. Radiocarbon-dating experts have also since adjusted their calibration methods, which makes the estimated ages of the sharks in the study slightly younger and with a larger margin of error.

However, Steffensen says the largest shark in the study was just 5.5m long, and he is fairly sure that they can grow past 6m, and possibly up to 7m. A clipping from a newspaper report from Dundee in 1895, for example, describes a huge Greenland shark landed by local fishermen that was 6.4m long. He shows me a rarely seen extrapolation of his graph to include bigger sharks, over 5.5m and beyond 6m – where the line heads way, way beyond 500 years, heading towards an astonishing 700 to 800 years. “When I found an old report of how big they could grow, I originally made a graph that ended at 1,000 years. I thought I couldn’t show it to anybody as they’d laugh at me,” he says.

So could the sharks really live for 1,000 years? “I think nearly – maybe not 1,000 years, but very, very old. Fish are always growing – growing until their last day. What is the likelihood that of the few hundred sharks that we have caught, we’ve caught one that’s the absolute maximum size?”

Some have suggested the copepod parasites that live on the Greenland shark's eyes may help keep the lenses clear over hundreds of years.

Some have suggested the copepod parasites that live on the Greenland shark's eyes may help keep the lenses clear over hundreds of years.

The eyes have it

The story of how Steffensen came to use eye lenses in his work is a rollercoaster ride. He had originally tried to date the growth rings of the sharks’ vertebrae using x-ray – a technique that had been used to age other marine vertebrates – but the Greenland shark vertebrae were too soft. Constant circulation contaminated the tissue with modern carbon, preventing him from attempting radiocarbon dating either.

The idea of using eye lenses came following a grisly murder case in Germany, where three dead babies were found in a freezer. German police approached Jan Heinemeier, a physicist at Denmark’s Aarhus University, as they searched for a way to age the bodies. He had recently published a paper suggesting that eye-lens crystallins – a set of proteins that remain stable for our whole life – could be used to precisely estimate a person’s date of birth using carbon-14 radiocarbon dating. Heinemeier’s method helped the police determine that two of the infants were born in the 1980s and one in the 2000s.

Steffensen then contacted Heinemeier and began to collect eye lenses from Greenland sharks, some from his own expeditions but many with the help of master’s student Julius Nielsen, who over the next five years collected dozens of lenses from sharks caught by various research vessels and fishing trawlers.

Professor John Fleng Steffensen (left), a biologist at the University of Copenhagen, has been studying the cold-water fish of the Arctic Circle since the 1990s.

Professor John Fleng Steffensen (left), a biologist at the University of Copenhagen, has been studying the cold-water fish of the Arctic Circle since the 1990s.

Once the group had a collection of Greenland shark lenses to study, disaster struck. The basement where the carbon-dating experiments were to be conducted was blown up in an accident involving dynamite, of all things, meaning they would have to find a different facility to take the measurements.

“It was another two years before we had the measurements,” says Steffensen with his head in his hands.

The secret to a long life

Recent work has shown that the Greenland shark has a vast genome – at 6.45 billion base pairs, it is the largest of any fish – which features extensive duplication of regions related to DNA repair. Steffensen says unique genomic features that aid DNA repair and tumour suppression are among many adaptations that enable the sharks to reach such long ages, including their huge size, low metabolic rate, ice-cold temperature, and high levels of the antioxidant and protein-stabilising compound TMAO. Greenland sharks also have a unique coronary circulation – unusual for a sluggish fish – which may be a requirement of having such remarkably low blood pressure and slow heart rate (just six beats per minute).

Recent work by Ewan Camplisson, a doctoral student at the University of Manchester, found that the activity of the Greenland shark’s metabolic enzymes does not seem to degrade over time, in contrast to the fall in metabolic efficiency that tends to be seen in most organisms as they age. Camplisson’s study also found that, perhaps surprisingly, the shark’s enzymes are not optimised for very cold temperatures – they are more active at higher temperatures. This is of particular interest given sea temperatures are expected to rise by several degrees in the next 100 years and the Arctic is warming faster than any other region.

Many more mysteries

While catching Greenland sharks to study can be surprisingly straightforward, and many sharks are caught as bycatch by fishing boats each year, videos and even photos of live sharks in the wild are rare. This means very little is known about the shark’s behaviour or feeding.

Their formidable jaws, which are used as saws by some indigenous peoples, are lined with backward-facing, razor-sharp teeth, meaning the shark can tear near-perfect circles out of the toughest flesh, leaving puncture holes in prey that look like the work of a giant hole-punch or cookie cutter. Satellite tracking data and their ultra-low metabolic rate suggest the sharks are extremely sluggish – perhaps moving at just one or two miles per hour and beating their tails just once or twice a minute. Although this would suggest they feed on carrion, telltale circular scars seen on the flesh of seals, whales and other sharks – plus countless squid beaks found in the sharks’ stomachs – suggest Greenland sharks also attack live animals. How they do this with physiology seemingly fine-tuned to work in slow motion is unclear.

As well as using radiocarbon dating to assess longevity, Steffensen and his colleagues use a range of experimental procedures to better understand Greenland sharks. These include tagging individuals with satellite pop-up tags to monitor their range and depth, and even wrestling sharks into a large floating respirometer to assess their resting metabolic rate (see image above). The team also constructed a special 4m-long cradle so they could analyse euthanised sharks at sea more carefully. On future expeditions, special deep-water cameras will be attached to baited lines at depths of up to 1,000m to film the sharks’ feeding behaviour.

Little is known about the worm-like parasites that live on the Greenland shark’s eyes either, and whether it is a parasitic or symbiotic relationship. Analysis of Greenland shark corneas suggests that the tissue is not scarred by the parasitism and that light is still able to reach the retina, although experiments show their nerve responses to flashes of light are among the slowest ever recorded in an animal. Some biologists have suggested that the copepod parasites may be beneficially bioluminescent, helping sharks attract prey or mates in the dark abyssal depths, although there is little evidence to support this. Steffensen, attempting to gather evidence for this during the endless day of the polar summer, once agreed to sit and watch the parasites in the only space they could find that was pitch black – the camp’s cold room. “We got our warm clothes on and sat in there for a few hours, and saw nothing,” he laughs. Another theory is that the parasites could act as window-cleaners, removing debris and refreshing the surface of the lens to help keep it functional over hundreds of years.

Steffensen’s next expedition will see him and a group of 22 biologists go out and fish for more sharks round the clock, for eight days. One of their key aims is to find individuals of different sizes to help fill in the picture of how the Greenland shark grows.

He hopes that future studies will be able to focus on telomere length and DNA methylation of the shark’s genome to further validate estimates of its longevity, and get more clues about how it protects itself from age-related degradation over such a long lifespan. He would also like to gather better tagging data, including the use of accelerometers, to better understand their movements in the ocean.

1) Nielsen, J. et al. Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). Science 353,702–704 (2016).

Tom Ireland is editor of The Biologist