Toads on roads

John P Sumpter explores one of the hundreds of schemes to help toads avoid heavy traffic in the UK

September 12th 2022

How many people love toads? The correct answer is ‘more than you might think’. The evidence comes from the many hundreds of ‘Toads-on-Roads’ schemes dotted around the UK. In densely populated and affluent countries such as the UK, road traffic is quite possibly the biggest threat faced by toads and other amphibians.

Adults undergo a spawning migration each spring, requiring them to travel from their terrestrial environment – they spend most of each year in woods, meadows and even gardens – to a pond or lake to breed. That return journey often involves crossing a road and therein lies the problem. Amphibians generally move slowly and their road sense is non-existent. The inevitable outcome is that many die on the roads, run over by traffic as they travel to their spawning pond or while returning from it. Between the towns of Henley-on-Thames and Marlow, in southern England, a large common toad population lives in an area known as Oaken Grove.

The woods in which the toads spend most of their lives are just north of a busy road, the A4155, whereas the lake in which the toads breed is on the south side of the road (see Figure 1.). Of all amphibians, including frogs and newts, toads in particular show extreme site fidelity, meaning that adult toads will almost always aim for the pond in which they were born to breed.

The Henley Toad Patrol volunteers use a roadside plastic barrier to help them to collect toads to transport across the road.

The Henley Toad Patrol volunteers use a roadside plastic barrier to help them to collect toads to transport across the road.

Tunnel vision

The A4155 is a relatively busy rural road – about 8,000 vehicles pass along it each day. Without mitigation strategies in place it is likely that the toad population would be quickly lost, as has happened to some toad populations in Cambridgeshire, where road deaths led to near extinction of the populations in just a few years[1]. The impact of road traffic on amphibians was observed to be a problem as early as the 1930s[2].

Concern for the toad population at Oaken Grove led to the creation of the first toad tunnels in the UK[3], an idea that had already found use in mainland Europe for over a decade previously. Two tunnels were constructed just below the surface of the road with an extensive fence erected to funnel the toads to the entrances. Although it is stated[3] that many toads passed through the tunnels in the year they were created, little subsequent information was gathered on how successful, or not, they were.

Recent evidence suggests that toads can be reluctant to use tunnels under roads and even when very large tunnels are created only a relatively small proportion of the toads that approach use them[4]. Without regular maintenance they also quickly become blocked. The need for a new approach led to the creation of the Henley Toad Patrol, now one of several hundred Toads-on-Roads schemes operating in the country.

Figure 1: The toads leave Oaken Grove to breed in the lake across the A4155. Two tunnels were constructed under the road, but the toads were reluctant to use them. Recently two new ponds were created in Oaken Grove in the hope that the toads would use these for spawning. However, most remain determined to return to the lake.

Figure 1: The toads leave Oaken Grove to breed in the lake across the A4155. Two tunnels were constructed under the road, but the toads were reluctant to use them. Recently two new ponds were created in Oaken Grove in the hope that the toads would use these for spawning. However, most remain determined to return to the lake.Catch and release

The schemes consist of groups of dedicated volunteers who collect the toads (and often other species of amphibians) and carry them across the road, releasing them in, or near to, their breeding pond. In the case of the Henley Toad Patrol, volunteers begin preparing in late January for the appearance of the toads. A relatively short permanent plastic barrier by the roadside is temporarily extended in both directions to create a plastic barrier of nearly 600 metres (see figure 1, above). Toads usually begin appearing at the barrier in early February, or occasionally in late January if the weather is mild. Members of the Toad Patrol then search along the barrier every evening until early April. They collect toads and other amphibians in buckets and transport them across the road, usually releasing them directly into the spawning lake.

Adult toads actually begin their seasonal breeding migrations in the preceding autumn, but cease moving in winter when it is cold, before restarting their migration as the weather warms. Toads are essentially nocturnal animals, and hence they do not begin appearing at the barrier until dusk, which in early February can be as early as 5pm. If the weather at that time is cold – below about 7°C – the toads stop moving. But if the weather is mild (>7°C), and especially if it is also raining, a lot of toads can be on the move. Knowing this, it is possible to have plenty of volunteers present when conditions suggest that a lot of toads will be arriving at the barrier.

If the temperature remains relatively high throughout the night, toads will be arriving at the barrier throughout the night. In this case volunteers usually go home before midnight, but then do an early morning sweep along the barrier to collect the ‘late arrivals’.

Toads in ‘amplexus’, with the female carrying the male

Toads in ‘amplexus’, with the female carrying the maleMigration patterns

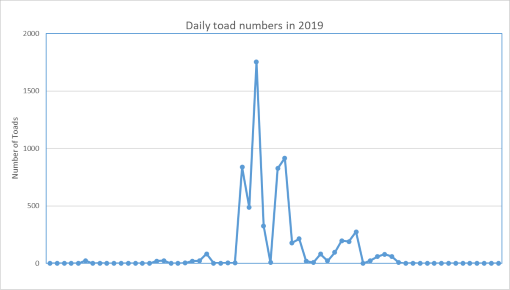

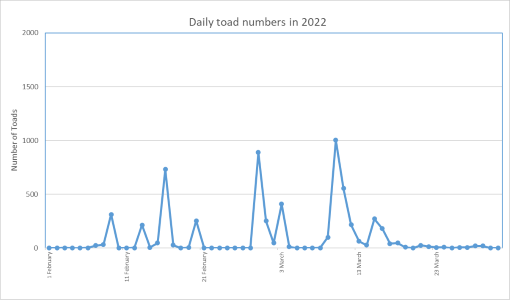

Mild, damp nights are reasonably unusual in February and March, so there are relatively few busy nights each season. On many nights not a single toad is collected, it being just too cold for an ectothermic (cold-blooded) animal to move. Then, on just a few nights each year, huge numbers can be seen (see figure 2 and 3, below). For example, on the busiest night in 2019, 20 volunteers carried 1,754 toads across the road. On two nights in the last 20 years that number has exceeded 2,000. In most years over 50% of all the toads are collected on just four or five evenings. It takes quite a few hours and many volunteers to collect so many toads.

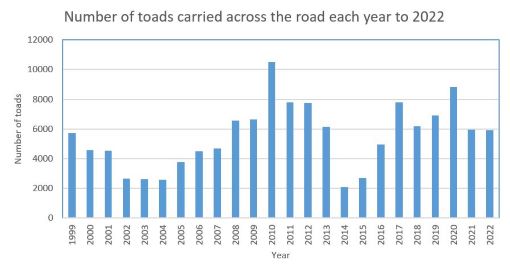

We have been consistently collecting data on toad numbers since 1999 (see figure 4, below). Volunteers very efficiently report their numbers to the author of this paper each evening, enabling daily and seasonal totals to be determined. This data shows that the size of the seasonal toad migration has varied five-fold in the last 24 years (1999 to 2022). The lowest total (2,088 toads) was recorded in 2014, while the highest total (10,501) was recorded in 2010.

The factors influencing the size of breeding migration each year are unknown, but these encouraging numbers suggest the toads of Oaken Grove are probably the largest accurately monitored toad population in the UK. The dataset is one of the longest, if not the longest, continuous dataset available for any amphibian in the UK (see also Reading and Jofré[5]).

In 24 years more than 132,000 toads have been carried across the road by volunteers, with the year average being just over 5,500 toads. Some of the volunteers report the sex of the toads they collect (sexing toads at spawning time is relatively easy), which has enabled a number of interesting facts about toad migration to be observed. One is that male toads migrate earlier than female toads.

Figures 2 & 3: The number of toads carried across the road by volunteers each night in 2019 and 2022, showing the highly variable number collected each night.

Figures 2 & 3: The number of toads carried across the road by volunteers each night in 2019 and 2022, showing the highly variable number collected each night.  Figure 4: The number of toads carried across the road by volunteers in each of the last 24 years.

Figure 4: The number of toads carried across the road by volunteers in each of the last 24 years.Fertilisation frenzy

At the beginning of the spawning migration nearly all the toads collected at the barrier are males – they want to be in the spawning lake when the females arrive. As migration progresses the larger females appear at the barrier. These are often carrying a male toad on their back. The pair of toads is said to be in ‘amplexus’, with the female carrying the male, often for many hundreds of metres, to the lake.

The male is, of course, trying to optimise his chances of fertilising the eggs released by ‘his’ female, although once in the lake other males will compete aggressively for the females. Single females arrive towards the end of the spawning migration, very plump and ready to spawn. Although toads dominate the spawning migration to this particular lake, good numbers of frogs and smooth (or common) newts are also collected by the volunteers from the barrier. As with the toads, numbers fluctuate considerably from year to year, but in most years around 500 frogs and 300 newts are helped across the road.

The toads spawn soon after reaching the lake. Although more male toads than female toads migrate each year – the ratio is often close to 2.5:1 – in an average year around 1,500 female toads spawn in the lake, together releasing over two million eggs. The females generally leave before the males, heading back towards the woods from which they came, crossing the A4155 en route.

Although the Henley Toad Patrol does not make systematic efforts to help these returning toads, volunteers do search the roadside verge for them and carry those they find back across the road. This year nearly 2,000 toads (about 34% of the spawning population that year) were helped across the road for a second time. It is extremely likely that some toads were helped both to the lake then back to the wood by the same volunteer. About half of these returning toads are expected to survive to spawn again the following year.

In April and May the lake is filled with toad tadpoles. Unlike frog tadpoles, they often form large aggregations. Once metamorphosis is complete – it takes about eight weeks on average – tiny toads, called toadlets, leave the lake. Instinctively they know which direction to head in: it is north to the woods – and the dangers of the road.

Usually, no organised attempt is made to help these tiny toads across the road – catching them is not easy – although in 2020, when there seemed to be an exceptionally high number of toadlets heading for the road, volunteers collected over 12,000 of them and released them into Oaken Grove woods. Fortunately, when toadlets are on the move between dusk and dawn in the spring it is in the middle of the night and traffic is considerably lighter.

Volunteer conservation groups across Europe are estimated to have moved millions of toads, and have helped provide data that shows large-scale and long-term declines in the common toad[6]. Many populations have declined in each decade since the 1980s to the extent that this common species now almost qualifies for International Union for the Conservation of Nature red-listing.

Citizen science success

In this context the Henley Toad Patrol is an example of citizen science at its very best. A group of more than 50 volunteers has successfully maintained this large toad population for decades. Without them it is highly likely that this very vulnerable population would have been lost due to unsustainable mortality from the road.

Although a strategy that involves lots of long cold nights by the roadside is not ideal, it is probably the only way of supporting this toad population. The only other practical approach is to create new ponds on the north side of the road, so that the toads do not need to cross a road in order to breed. This has, in fact, already been initiated, with two ponds created within Oaken Grove a few years ago. However, while some toads have begun to breed in these ponds, most appear to ignore them and head for their ancestral breeding lake – and the road. Toads are obviously very determined creatures.

John P Sumpter FRSB is a research professor within the Division of Environmental Sciences, Department of Life Sciences, Brunel University London.

The Henley Toad Patrol thanks the Culden Faw Estate for allowing its activities to take place every year. The author thanks all members of the Henley Toad Patrol, in particular Angelina Jones, who recruits, trains and organises the volunteers every year; and to Cathy Holwill, who has probably carried more toads across a road than anyone else in the UK in the last decade. He also thanks Tamsin Runnalls for help with the preparation of this article, Allan Staley and other members of the Henley Toad Patrol for the photographs, and Fraser Arpino for providing Figure 1.

1) Cooke, A.S. The role of road traffic in the near extinction of common toads (Bufo bufo) in Ramsey and Bury. Nat. Cambs. 53, 45–50 (2011).

2) Beebee, T.J. Effects of road mortality and mitigation measures on amphibia populations. Conserv. Biol. 27, 657–668 (2013).

3) Langton, T.E.S. Tunnels and temperature: Results from a study of a drift fence and tunnel system at Henley-on-Thames, Buckinghamshire, England. In Langton, T.E.S. Amphibians and Roads (edited), 145–152 (ACO Polymer Products Ltd. England, 1989).

4) Ottburg, F.G.W.A. & van der Grift, E.A. Effectiveness of road mitigation for common toads (Bufo bufo) in The Netherlands. Front. Ecol. and Evol. 7,

article 23 (2019).

5) Reading, C. J. & Jofré, G.M. Declining common toad body size correlated with climate warming. Biol. J. Lin. Soc. 134(3), 577–586 (2021).

6) Petrovan, S.O. & Schmidt, B.R. Volunteer conservation action data reveals large-scale and long-term negative population trends of a widespread amphibian, the common toad (Bufo bufo). PLOS ONE 11 (2016).