Black History Month: Biologist and activist Margaret Collins, AKA 'the termite lady'

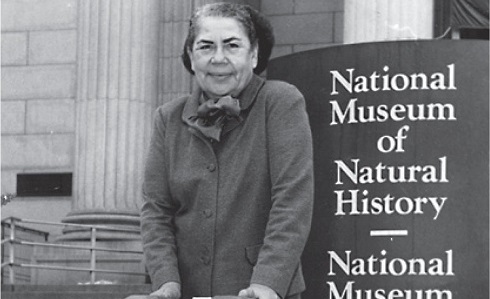

Margaret Collins in 1991 pictured outside the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington D.C. Image courtesy of Herbert and Veronica Collins with thanks to Vernard Lewis.

The Biologist explores the USA’s first Black female entomologist, Margaret Collins, whose remarkable research career dovetailed with a constant fight for the rights of African-Americans

October 5th 2022

While all academic careers can be challenging, it’s fair to say Margaret Collins endured more challenges than most: as well as taking long breaks from her research to campaign for civil rights and protest against segregation, she faced sexism and racism from colleagues throughout her career, intimidation from police and the FBI, and even a bomb threat to try and stop her giving lectures. She still became one of the world’s leading experts on termites.

Born by the banks of the Kanawha river in the West Virginian town of Institute in 1922, Collins was fascinated by wildlife from an early age. Inspired by the naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton’s books on scouting, wild living and naturalism (also cited by David Attenborough as an inspiration), she would collect insects from the barns, woods and pools nearby, or explore the shores of the Kanawha where it wound past the family yard.

Decades before the civil rights movement helped to secure the Civil Rights Act of 1957, Black people in the USA were still routinely denied access to education and well-paid jobs and lived under the threat of harassment and violence. However, Collins’ upbringing was unusual in that Institute was both an all-Black town and a college town, and her father was a professor of agriculture and taught biology to local students.

Recognised as a child prodigy at just six years old, Collins was given access to West Virginia State University’s book collection, and using academic texts aimed at people three times her age, began identifying the insects she collected. At just 14 she had graduated high school and began studying biology at West Virginia State College on an academic scholarship.

She initially struggled to attract mentors in the male-dominated and overwhelmingly white field. Black people were not allowed to actually attend the University of West Virginia, and were instead given a small fee to study out of state – and Collins struggled to make ends meet. Eventually she tracked down another young Black biologist, Toye George Davis, who helped her continue to identify specimens and gave her a part-time job. When Davis was drafted to the army during WWII, he asked a Jewish refugee called Frederick Lehner to take over as her mentor – her first ever white teacher.

Collin's research became a definitive source of information on the behaviour of termites.

Collin's research became a definitive source of information on the behaviour of termites.After graduating, she enrolled in graduate school not expecting to earn an advanced degree but simply to learn enough about collecting to start a business selling specimens to biological suppliers. But after studying under the revered zoologist Alfred Emerson, she was inspired to pursue research. Noticing her talents and passion, Emerson assigned Collins to look after his termite collection and paid her through an assistantship to help her financial situation. (She also read ‘every book’ in his vast personal library). In 1950 she received her PhD from the University of Chicago. She had become not only the first Black female entomologist in the US, but also just the third Black female in the entire field of zoology.

Her thesis, ‘Differences in Toleration of Drying among Species of Termites,’ became known as the definitive source of information on the subject. Termites play a key role in many soil ecosystems, as well as causing billions of dollars’ worth of damage to buildings and crops, and Collin’s work proved vitally important in better understanding both.

Research trips to Florida and the Caribbean, often self-funded, became a feature of her career and she became the leading expert on termite diversity in this region. During her research expeditions to Guyana, she helped the island’s military to build in ways that would avoid termite damage, and devised ways to use termite excretions to strengthen building materials. She co-authored over 40 publications on the biogeography, physiology, defence systems and taxonomy of termites; discovered a new species (Neotermes luykxi), as well as having another named after her (Parvitermes collinsae).

She spent 35 years as a professor of zoology at three universities, became president of the Entomological Society of Washington, and took various other prestigious roles including as a senior research associate at the Smithsonian Institution, dean of the zoology department at Florida A&M University and chair of the biology department at Florida A&M University. This was, of course, all achieved against the backdrop of either overt oppression of Black people or a rising backlash as the civil rights movement gained momentum.

In the early 1950s, when Collins was invited to give a lecture at a nearby university, the school received an expletive-laden bomb threat by phone. The caller said that if she dared speak at the ‘white university’ then the entire science building would be blown up. Bizarrely, Collins herself searched the building to ensure there was no bomb, but the invitation was withdrawn as the university feared for the safety of its students.

Collins pictured dissecting a termite nest with her grandson in 1996. Image courtesy of Herbert and Veronica Collins with thanks to Vernard Lewis.

Collins pictured dissecting a termite nest with her grandson in 1996. Image courtesy of Herbert and Veronica Collins with thanks to Vernard Lewis.In 1956, when students in Florida began to boycott the bus companies in Tallahassee that still insisted on segregating riders by race, Collins offered her support by driving the protestors back and forth to college or work. She was followed and at times chased by local police, state police, and even the FBI. Lynch mobs, often involving local police, were still terrifyingly common. Despite the intimidation, Collins still helped transport the protest organisers’ secret documents to a safe location just before their headquarters were raided by authorities.

Having consistently published one or two papers a year, she published nothing between 1952 to 1957 as her role supporting the snowballing movement took priority. “I had to do what I thought was the most important thing,” she recalled in an interview for the book Black women scientists in the United States. “That’s all there was to it.”

Her exhausting double life and two divorces took their toll on Collins, and she recalls going hungry in order to ensure her two children were fed. But her activism continued throughout her career, and in 1979 she organised a symposium on “Science and the Question of Human Equality” for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which led to the publication of a book of the same name.

Collins retired from Howard University in 1983 but continued to conduct research for the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, where she had contributed immensely to the termite collection. Like her Black mentors before her, she had created an inspiring path for the next generation of Black entomologists to follow. She died aged 73 in April 1996, in the Cayman Islands. She died, as she had hoped to, while out in the field looking for insects.

Tom Ireland is editor of The Biologist

Lewis, V. Child Prodigy, Pioneer Scientist, and Women and Civil Rights Advocate: Dr. Margaret James Strickland Collins. Florida Entomologist 99(2), 334-336 (2016).

Strickland, M. Differences in Toleration of Drying among Species of Termites. Ecology 31(3) 373-385 (1950).

Collins, M, Wainer IW and Bremner TA. Science And The Question Of Human Equality. Routledge (1981).

‘Termite Expert Margaret Collins Dies During Trip.’ Washington Post, 5th May 1996.