Biodiversity on ice

5th December 2025

Tom Ireland visits two of the world’s largest biobanks and explores their remarkable efforts to store and restore Earth’s biodiversity

Fifty years ago, pioneering zoologist Kurt Benirschke began cryopreserving cells from rare and endangered animals that had died at San Diego Zoo. Back then, in 1975, little could be done with frozen animal cells beyond research to better understand chromosomes, and few would have predicted that rising rates of species loss would escalate into a period of biodiversity decline rivalling Earth’s major mass extinction events. Benirschke’s collection became the foundation of what is now known as the ‘Frozen Zoo’, one of the world’s largest and most advanced animal biobanks. A quote on the wall of the facility still reads: “You must collect things for reasons you don’t yet understand.”

This year also marks the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Millennium Seed Bank, a vast, purpose-built, disaster-proof vault for the long-term storage of seeds. It contains 2.5 billion seeds, representing more than 40,000 species from around the globe. This bunker in the Sussex countryside is technically the most biodiverse place on Earth.

Advances in molecular, genetic and reproductive technologies mean there is now a huge range of uses for biobanked material, from basic research to biotech-assisted reintroduction programmes.

The Biologist was fortunate enough to speak to the two women in charge of these extraordinary collections to understand the science of biobanking and how readers can help add to their collections.

Established: 1975

Stores: Animal cell cultures, eggs, sperm and embryos

At: -196°C

Specimens: Approximately 12,000

Species: 1,300+

The San Diego Zoo’s Frozen Zoo was founded in 1975. As well as being the largest animal biobank in the world, the Frozen Zoo has been involved in developing cutting-edge technologies to reintroduce lost biodiversity, and is a world leader in cryopreservation methods for different animal cells and gametes. In 2020 a cloned foal of the critically endangered Przewalski’s horse was born from cells that had been cryopreserved by the Frozen Zoo back in 1980.

Marlys Houck, Curator of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Frozen Zoo

The vast majority of our earliest samples were from mammals. They mostly came from the San Diego Zoo, then from other zoos in North America, so we have a large representation of animals that have been in North American zoos.

We’d like to increase the number of animals that aren’t typically found in managed collections. We only have about 30 species of amphibian. They’re in rapid decline so we would like to increase the number of their samples. We’re also working with partners such as the US Fish and Wildlife Service to sample the species they manage such as the whooping crane, which we added this year.

Our reproductive sciences team has been working to expand the collection to include invertebrates as well. They’re working to develop methods to bank viable larvae for sea stars and gametophytes of kelp. These are organisms for which there are few known cryopreservation methods.

Working with our partners is really important. We want to partner with people who might have access to animals that aren’t in our collections. Samples can be taken during medical procedures, shortly after death or even just when ear notches are made to help identify animals. However, the most important thing we can do is help set up other biobank collections around the world, with people trained and stationed in biodiversity hotspots, so we don’t have the issue of everything having to be shipped across the world to us.

When the last animal of a species dies or there is just a handful of animals left, and you’ve never banked it before, the pressure is intense. You search the literature, you talk to others and you find out as much as you can. For example, we were able to get a sample of the vaquita [a porpoise now down to fewer than a dozen individuals], which no one had ever frozen before. We looked at the process for the closest related individuals, like dolphins, and we adapted it from there. There’s a lot of trial and error involved.

We received the last ever Hawaiian songbird when it died. At that time we weren’t even doing birds, only mammals. I had grown cells from new feathers of birds, but this didn’t have new feathers, and I knew bird skin doesn’t grow very well. I tried the cornea, but it was too small. So I just took samples from the front of eye, back of the eye, kidney, liver, spleen, gonads. The only thing that worked was, oddly enough, the back of the eye. The eye is now one of our preferred tissues from a bird and the trachea is the other. These tissues repair quickly, and that’s what our process is – trying to get cells to grow and divide quickly.

San Diego Frozen Zoo is one of the world’s largest and most advanced animal biobanks

San Diego Frozen Zoo is one of the world’s largest and most advanced animal biobanks

The black-footed ferret is a great example of biobanking as a tool to facilitate recovery. Our Frozen Zoo cell lines have been used to feed back genetic diversity into the tiny captive-bred population, which lives in proximity to its native range and has an ecological role.

We couldn’t have imagined 50 years ago all that’s happening now [in biotechnology]. I really would like to be here 50 years from now to see how the cells are going to be used.

In the beginning all of our samples were in one cryotank and it was lost with 300–350 samples in it. That was an extreme wake-up call. The first thing we did was set up two duplicate tanks on separate power systems. They are now a 40-minute drive apart. We have emergency power, but if the power goes out we still have a three- to 10-day window as long as the liquid nitrogen remains. We have security teams and alarms, and we can even observe on our phones what’s going on in the middle of the night.

We started really small, and I think that’s the way for everybody to get started. If you can freeze five samples a year, that’s five more that you would have had, perhaps in an area that’s underrepresented in our collection.

There are now methods that enable you to process samples in the field – one of our collaborators called it ‘express banking’. It takes one hour instead of four or five weeks, and then you can store it for as long as you’re in the field. So we want to help people understand that starting on any scale will really help the effort. If we all work together, we can really increase the number of samples that are banked.

Established: 2000

Stores: Seeds

At: -20°C

Collections: 102,467

Species: 40,000+

The idea of a purpose-built seed bank at Kew’s Wakehurst site was first conceived in 1997. As well as its disaster-proof vaults and suite of seed biology labs, the facility’s staff work with people in over 100 countries to help safeguard as many species as possible. Almost all of the UK’s native plant species are preserved in the seed bank.

Sarah Gattiker, Seed curation manager, Millennium Seed Bank

Seed banking is a really easy way to protect plants because seeds are designed to be stored. We’re a global project, currently working with over 40 partners, but we’ve worked with more than 275 since the start of the project. Kew doesn’t own most of the seeds, we just care for them. We have that written into all the legal partnerships.

I always joke that it’s a little bit like Christmas. A box will arrive, and it’s not until you open it that you find what’s inside. It might be incredibly rare flora from Madagascar, a packet of tiny capsules from the Scottish mountains or loads of crab apples from a UK collecting partnership. Occasionally we get sent old collections of seeds that have been discovered – for example, the seeds that were found in a Bible that had not potentially been opened for over 100 years.

The first stage after unpacking is to dry the seeds. That really gives them longevity. Then we clean them, using various techniques based on years of gathered and shared experience. We will keep some debris in the collection if it means not compromising the genetic diversity of the collection.

We select a small sample of seeds that represent the diversity of the collection for quality checking. The sample is x-rayed for signs of infection, such as insect larvae, and to check for embryo and endosperm development. If a seed cannot be x-rayed because it is too small or in a complex fruit, we do cut tests instead. All this goes into our database and informs what we do further down the line. If the partners have agreed, the data can be made available worldwide. We’re open to sharing information for the sake of global biodiversity.

The Millennium Seed Bank at Kew holds more than 40,000 specimens

The Millennium Seed Bank at Kew holds more than 40,000 specimens

Once they’ve spent at least a month in the freezer we start germination testing. It’s one of the elements of the job I love the most, because it involves problem solving – we’re trying to recreate conditions from all over the world. Is it an alpine species that needs to sit in the snow for three months? Or does it need to warm up? The incubator in front of you is running at 40°, and it’s next to one that’s running at zero.

We have an enormous workload, doing thousands of germination tests a year, both before and after storage. The majority of our collections germinate well after long-term cold storage, both at -20°C or cryopreserved. We’re just exploiting what seeds naturally do – trying their best to protect themselves.

The collecting data is super important to us. Were they in a woodland, an alpine meadow? Were they on a rock face? What aspect were they facing? All of that gets recorded and put into the database.

Maybe 8% of seeds are not bankable. We are now proactively trying to protect these ‘recalcitrant’ species with cryopreservation techniques.

When the seeds get to the vault, they’ve been dried, cleaned, x-rayed and counted, so we know the quality and quantity. Then they can come down here for storage. You’re effectively standing in the most biodiverse place in the world because of the number of species we have in these rooms – over 40,000.

It’s kind of apocalypse-proof down here. We have radiation sensors on the roof, and if they’re triggered, the air supply is cut. Not so good for staff, but helpful for controlling the air being brought into this room. There are flood barriers around the room, and we’re built into the ground under a huge amount of concrete, so technically you can crash an aeroplane on top of this and this room will be safe.

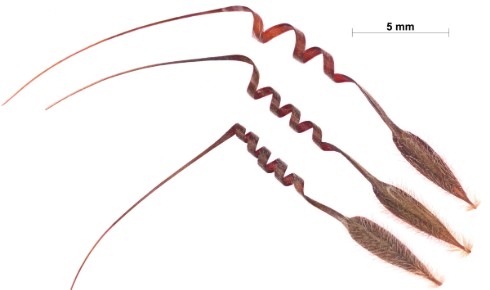

Seeds of Pelargonium elongatum

Seeds of Pelargonium elongatum

We came through a big vault door, which is locked at night. It’s a very controlled space, but [even in the] worst case scenario it actually takes quite a long time to even get above zero because the thermal mass in there is massive. It stays really cold as long as you don’t open the doors.

Scientists and researchers request seeds quite a lot. You get little surges in September or October, when research programmes tend to start. The seeds can also just be needed for restoration – you might be creating a seed mix that’s going to go back out to create a landscape. Collections can be used for a wide variety of purposes such as filming, education and display in other botanical gardens.

I’m very fond of alpine plants. They’re small and beautiful and it’s such a lot of work to have banked seeds from regions such as the Arctic or Antarctic. I feel quite passionate about protecting them, because they’re living on the edge, literally. And if we can try to save them, often they will be quite happy being saved.

There should be no good reason now why any plant should go extinct. If we can get to them in time, we can protect them. We hold plants here that have gone extinct in the wild, and we can bring them back to life.

We’re always trying to make seed banking accessible whatever budget you have. We run training courses throughout the year and online. We help train other seed banks, help with their design, and we run seed conservation courses. We’ve taught thousands of people seed banking, then they teach each other. It’s a fully supportive network.

Find out more about San Diego Frozen Zoo and Kew's Millennium Seed Bank.

Tom Ireland is editor of The Biologist