Decolonising bioscience

Above: An image of of Graman Quassi, a fascinating but largely unknown 17th century botanist and emancipated slave who described important medicinal plants centuries before they were 'discovered' by European researchers.

Ten years after the idea of decolonising higher education emerged from protests in South Africa, The Biologist explores to what extent bioscience curricula in the UK have been ‘decolonised’

In 2015, students at the University of Cape Town began to demand that a statue of the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes be removed from their campus. Rhodes, a mining magnate turned politician, established British rule across vast swathes of Southern Africa, and forcibly removed land and rights from Black Africans while prime minister of the ‘Cape Colony’.

The protests quickly spread to institutions in other countries. Campaigners wanted not just to remove the physical symbols of colonialism, slavery and apartheid that still adorned their university campuses, but to ensure that education was freed from colonial worldviews and biases, and the teachings that perpetuate them.

Within a few years, many higher education institutions and organisations around the world were discussing the concept and developing guidance to help staff ‘decolonise’ their curricula. Decolonising became less about toppling statues or cancelling imperialists, and more about recognising the historic links between science and colonialism, and how it still influences how scientific knowledge and data is produced.

In the biological sciences, there is no shortage of topics requiring reflection – whether it be the exploitation of natural resources from colonised regions; the use of biological pseudoscience to justify racism and slavery; the unethical experiments conducted on Black people in the 20th century; the continued dominance of white European samples in genomic datasets, or the disproportionate impact of climate change on former colonial nations, to name just a few.

But ten years on, it’s unclear to what extent decolonisation still features in efforts to make university education more inclusive. As part of Black History Month 2025, The Biologist spoke to several leaders of work in this field to understand if ideas about decolonising have changed, or if it is still a concern in bioscience departments across the UK. A number of key themes emerged from our conversations.

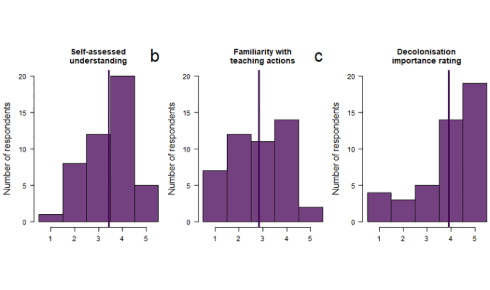

In ‘Exploring attitudes to decolonising the science curriculum (Grinsted et al 2024)’, a survey of higher education staff found high levels of understanding of decolonisation and ratings of how important decolonising the science curriculum at their institution is, but lower levels of familiarity with actions required to improve content and delivery.

In ‘Exploring attitudes to decolonising the science curriculum (Grinsted et al 2024)’, a survey of higher education staff found high levels of understanding of decolonisation and ratings of how important decolonising the science curriculum at their institution is, but lower levels of familiarity with actions required to improve content and delivery.

A patchwork of progress

In the UK, the most recent Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) benchmark statements for biosciences and biomedical science clearly state that degree programmes should “critically engage with how the subject has contributed to and benefited from social injustice, for example presenting a balanced and informed history of the field and acknowledging that influential scientists might have benefited from and perpetuated misogyny, racism, homophobia, ableism and other prejudices”.

Yet decolonising is an activity that relies on educators with a particular interest or enthusiasm to lead change in this area. With little central organisation or guidance, it has been largely left to frontline staff to implement themselves. The result is huge variety both between and within higher education institutions.

Departments, schools or subjects with staff who are interested and motivated to lead this work may be several years into their decolonising efforts, while those without such staff may not have done anything beyond more general university-wide equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) initiatives.

Competing priorities

Academics and educators are feeling the pressure at work, from cuts to funding and staff, to unprecedented levels of paperwork and admin. Many simply don’t have the capacity to organise and conduct additional audits and reflection exercises of themselves and their colleagues. Other areas of EDI work are seen as more urgent by university administrators – especially those where there is the risk of discrimination litigation.

Resistance – or just indifference?

Staff leading decolonising work report general support for their work, albeit with resistance from a minority of colleagues.

But some have been surprised at the lack of enthusiasm from their students. There is also a growing population of students who actively oppose the discussion of racism and colonialism in their education, according to educators.

"Every year we try and recruit students to form their own subgroup to chat about these issues or run their own surveys and tell us how they would like to co-create, or what opportunities there are for developing this work…But it does depend on students getting involved, and their background knowledge as well. So some years we have students that are really engaged and want to do something. Other years, less so, or their focus is elsewhere, like neurodiversity or accessibility."

"Students get portrayed as being really progressive and really left-wing and constantly wanting change. Actually, we have a massive amount of students that either don't care or don't really think about it, and also students right on the other side that are completely against any sort of change."

Confidence and skills

Some educators find it difficult or worrying to delve into politically or socially sensitive topics without adequate training. Even with the best intentions, talking about race can heighten tensions among students. A survey of science educators at one UK higher education institute in 2024 found that although the majority recognised the importance of decolonising, far fewer were familiar with the actions required to enact it.

James Cook's 1768 voyage of exploration around the islands of the Pacific was both a scientific expedition, funded by the Royal Society, and a mission to find lands that could be claimed by the British Empire.

James Cook's 1768 voyage of exploration around the islands of the Pacific was both a scientific expedition, funded by the Royal Society, and a mission to find lands that could be claimed by the British Empire.

One senior lecturer told The Biologist that her first foray into discussing decolonisation in lectures actually led to racist comments being posted on a student forum, and then accusations that it was her fault.

Another wrote:

At the same time, political movements with an explicit ‘anti-woke’ agenda are having a moment across the US and Europe, which makes decolonising activities quite literally a risky pursuit in some parts of the world.

The clearest impact of this can be seen in the US, where academics risk losing their funding or their jobs if their work focuses on certain themes, or even particular words and phrases.

Misconceptions and shifting terminology

There is still a misconception that decolonising is about toppling statues and deleting references to scientists with links to colonialism, racism or slavery. It isn’t – it is about recognising those links and adding the contributions of people or cultures who have been omitted or silenced.

For the reasons listed above, the term ‘decolonising’ is seen by some as unhelpful or too politically loaded. As a result, some decolonising work may be continuing but under a different banner or terminology, such as ‘diversifying’, ‘introducing global perspectives’, ‘multiperspectivity’ and ‘ethical, equitable, accessible and inclusive curriculum and assessment’.

Although diversification of resources such as reading lists can be the first step in decolonisation, contributors were keen to stress that diversifying and decolonising are not the same thing.

Unsung hero Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, one of the most important in medical research

Unsung hero Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, one of the most important in medical research

Looking beyond bioscience

Decolonising expert Peter d’Sena, a professor of history and education at the University of Hertfordshire, says that the issues and lessons around decolonising education are broadly similar across different subjects. He advises looking for support and resources outside of the biosciences, such as the Royal Historical Society’s Race Report and the Royal Geographical Society, which he describes as being “streets ahead” of other subjects in decolonising geography education. Some lecturers in the biosciences have invited historians to collaborate and give guest lectures that can help bring the links between colonialism and science to life.

An ongoing project

The biosciences have long and deep historical links to colonialism, but there are plenty of contemporary issues that requires continued effort to reshape. Whether it be ‘helicopter research’ – where researchers in high-income countries conduct studies in low-income countries without meaningful involvement or benefit to local communities – or the continued use of unscientific racial categories in research and datasets – decolonising biology is an ongoing project. Decolonising work is about preparing the scientists of the future to drive positive change in a diverse and globalised world.

Manchester Met Decolonising Tool Kit

DeMontford University decolonising resources and publications

Decolonising Bioscience Curricula at Bristol University

Decolonising and diversifying bioscience education from the Society for Experimental Biology

Kingston University: Decolonising the science curriculum

Times Higher Education – Decolonising the curriculum: how do I get started?

Decolonising the Curriculum – Sharing Ideas. A series of podcasts by The Race Equality and Anti-Racist Sub-Committee (REAR) at The University of Edinburgh

Decolonising: The importance of teacher training and development

Exploring attitudes to decolonising the science curriculum—A UK Higher Education case study

Tom Ireland is editor of The Biologist