Dogs for Diversity

When university administrators said Joey Ramp could not bring her service dog into the lab, she kitted him out in full protective equipment and fought to overturn their decision. Now she is helping create more inclusive policies on the use of service dogs in science

February 7th 2020

To embark on a neuroscience degree in my mid-40s was challenging enough. Doing so after becoming disabled following an accident in 2006, which left me with 23 broken bones, fractured vertebrae, nerve damage, a head injury and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD), made that task even more arduous. However, the biggest obstacle I faced during my entire time in academia was not the coursework or the rigorous schedule of research, but the fact that I was a student with a disability and a service dog (SD) handler.

For more than a century dogs have proven successful as assistive devices for people with disabilities, dating back to the start of the modern-day guide dog. An SD is considered medical equipment and helps its handler lead an independent life. Over the last four decades there has been a steady increase in the use of SDs to mitigate various disabilities, as well as a steady increase in students registering for disability services at university level.

Access to hands-on laboratory experience is crucial to earning an undergraduate degree in STEM, yet SD handlers are frequently barred from these opportunities. As the number of SD handlers in our communities increases and the number pursuing STEM degrees on university campuses rises, it is important to develop inclusive laboratory SD policies.

Joey Ramp with her service dog Sampson (image courtesy of Thompson McClellan Photography)

Joey Ramp with her service dog Sampson (image courtesy of Thompson McClellan Photography)In the USA there are ambiguous federal laws that are written to protect the rights of SD handlers to access everywhere the general public is allowed to go. There are additional federal and state laws and policies that are meant to protect the rights of SD handlers in education. Yet there is a mismatch when these laws are applied to core-course laboratories. Interpretation of these laws and policies by a university professional becomes just that – an individual’s interpretation. Students are often reluctant to challenge a university administrator or faculty member.

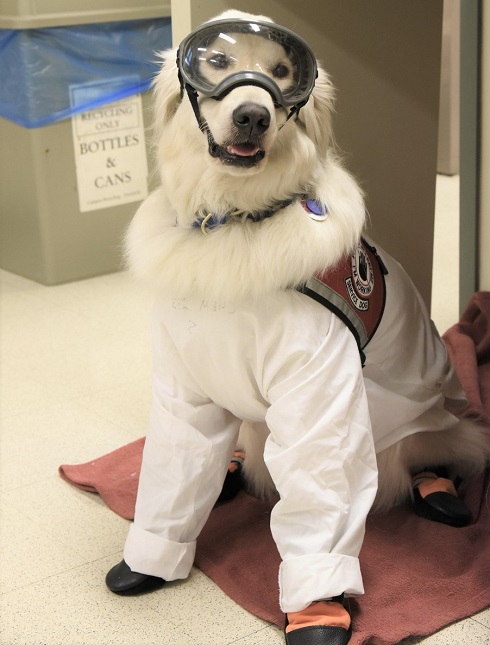

In my first year of college I was told that I must change my major because an SD would never be allowed access to a laboratory environment. Rather than taking that advice, I outfitted my SD (Theo) with exactly the same personal protective equipment (PPE) that I wear: goggles, boots and a lab coat. We successfully completed two years in general chemistry courses and an organic chemistry course. When I retired Theo, my second SD (Sampson) took over assisting me on a daily basis.

My SDs became the first in the 150-year history of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) to be allowed access to core chemistry and biology laboratory courses, and then eventually into the Rhodes Laboratory, a neuroscience research laboratory at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. This was ground-breaking.

Canine conundrum

This progression did not come without significant resistance by some science faculty and university administrators. Every semester involved hours of meetings repeatedly addressing the same concerns. One faculty member involved with a behavioural neuroscience course slammed her fists on the desk and yelled at me in frustration. She was not the first and would not be the last, and believed that my SD would be detrimental to conditions in the rodent laboratory during the course.

Sampson is trained to retrieve items differently when working in a lab that may contain hazardous chemicals (image courtesy of Doris Dahl)

Sampson is trained to retrieve items differently when working in a lab that may contain hazardous chemicals (image courtesy of Doris Dahl)Although there is ample literature to support the idea that cats affect rodent stress levels, there is only one such experiment, to my knowledge, that used direct exposure to canine scent. The results showed the same anxiety and stress effect on the rodents (or less in the case of an altered canine) as that of the presence and handling by a male experimenter, but not a female experimenter[1].

The faculty member refused to allow me to proceed in her course with the assistance of my SD and her lack of effort in trying to make it work was frustrating. However, rather than deter me, it fuelled the fire of curiosity. Using my experience I began to advocate for other SD handlers’ accommodations in science. I secured independent funding for a two-year research study to test the effect of an SD on rodent physiology and behaviour. Dr Justin Rhodes (Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology) and I developed a protocol looking at stress models on rodents when an SD was present in one room and not present in the control room.

The purpose was to test not only the scent exposure of a canine, but also the visual stimulus of having an SD present in the room, with no direct contact between the rodents and the SD. To determine the level of stress reactivity we would record ultrasonic vocalisations of the rodents and test their blood corticosterone levels. The gathering of this data would help in making more informed decisions on whether to allow an SD into an animal facility or laboratory that used rodents.

However, over the course of 18 months the relevant committee on animal use refused approval for us to proceed three separate times, stating there was a lack of scientific merit. To date, this research study has not been allowed to proceed, with the committee stating in an email that students who were SD handlers would not be seeking these opportunities. Yet other universities that have SD handlers enrolling in laboratory courses have contacted us directly asking for the data we were unable to collect.

Unequal opportunities

Scientific organisations and institutions place a priority on the recruitment of a diverse population in STEM, with diversity and inclusion both topics that educational institutions talk about frequently and passionately in the recruitment of students. Yet often the follow-through is lacking. Student SD handlers frequently feel unsupported by their science faculty and are advised against pursuing an education in STEM, which is counter to equal-opportunity initiatives.

I realised that the development of a more diverse and inclusive atmosphere within STEM careers begins with the administration. This inclusive atmosphere and attitude trickles down into practical changes at the undergraduate level in the core science courses that include laboratory components.

Accommodations require minimal alterations, if any, to the normal flow of core-course laboratories. The steps could include outlining skills an SD would need to master before entering a laboratory environment – for example, wearing PPE, lying under a bench, staying on a mat for up to four hours and not automatically retrieving items from the floor without a command. This places the responsibility for the training of the SD solely on the handler, which also minimises the legal risk for universities.

Accessibility barriers

I have since graduated in biocognitive neuroscience with high distinction in research. I continue to work in the Rhodes Laboratory as a neuroscience research affiliate with Sampson by my side every day. He is considered the ambassador for SDs in science and is well known on social media. He won the 2018 American Kennel Club Award for Canine Excellence for his part not only in my success as a neuroscientist and advocate, but also for his daily assistance to me as a person recovering from a head injury, C-PTSD, and living with chronic physical limitations.

Joey Ramp wants to see research conducted on how the presence of a service dog effects rodent studies. (Image courtesy of Doris Dahl)

Joey Ramp wants to see research conducted on how the presence of a service dog effects rodent studies. (Image courtesy of Doris Dahl)I was offered a position from a principal investigator and a full scholarship, but my graduate work has been put on indefinite hold. Research into the neurological underpinnings of PTSD after brain injury was the reason I started down the path of neuroscience, but I am not proceeding with graduate work because of the barriers for SD handlers in science animal research facilities.

I recognise that more research needs to be conducted to determine the impact an SD would have on rodent physiology and behaviour, and cannot understand why a study to determine just that will not be approved. I have since developed a consulting company that helps student SD handlers and educational institutions navigate accommodations for SD handlers in science[2], mediating between students, administrators and faculty. Since not all laboratory environments are safe for an SD and handler, I conduct individualised risk assessments to determine what would be appropriate accommodations in a laboratory environment.

I have been working with universities nationwide to develop laboratory SD policies that will provide student SD handlers equal opportunities in science.I do this so that no other student SD handler wishing to pursue a career in STEM will have to navigate the university system and face the resistance and obstacles that I did.

I am also the co-founder/vice-president of the International Alliance for Ability in Science[3], a non-profit organisation that helps provide students with disabilities, university faculties and administrators, with resources to assist in navigating accommodations in science. Science faculties can’t ignore disabled student SD handlers and hope they go away. Policies are changing more rapidly now than ever. Accessibility options (primarily technology) are expanding at a rapid rate.

It is time for open-minded communication and collaboration to make policies workable for every student. It is time we as science professionals take the initiative to bring all qualified scientists, including those who are disabled and SD handlers, to the table by developing inclusive laboratory SD guidelines and policies, and making reasonable accommodations.

This is diversity and inclusion in action.

Joey Ramp is founder of Empower Ability Consulting and vice-president of the non-profit International Alliance for Ability in Science.

Thanks to J S Rhodes, C G Parker, P Malik and M Ginsberg for their contribution to this article. Follow Sampson’s work on Twitter via @sampson_dog

This article appears in the Feb/March issue of The Biologist (67.2).