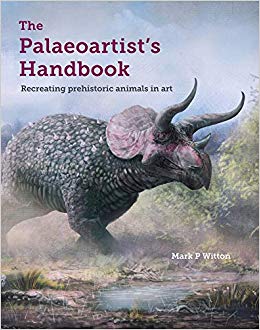

The Palaeoartist’s Handbook: Recreating Prehistoric Animals in Art

Mark P Witton

The Crowood Press, £22.00

Mark Witton’s reconstructions of ancient animals have appeared on television, in museums, in scientific journals and books, and in magazines, including The Biologist. The pterosaur researcher, author and artist has now produced what is thought to be the first comprehensive guide to reconstructing prehistoric animals through art.

To call it a ‘handbook’ for palaeoartists seems to undersell this fantastically thorough (and large) book, which contains hundreds of beautiful illustrations and sections on the history and theory of palaeoart.

The bulk of the book focuses on the key principles of reading fossil evidence for clues to appearance. There are chapters on guts, muscles and fatty tissues; skin and colouration; facial tissues; and ancient landscapes. This being an art form as well as a science, there are chapters covering composition, poses, style and mood too.

The level of detail is impressive. For example, the segment on skin alone provides guidance on determining skin texture, scale size and shape, the presence of armoured skin, the size and shape of fins and flippers; the characteristics of hair, fur, beaks, claws, and other projecting structures such as soft-tissue horns and crests; and, of course, those much-debated filaments and feathers.

Introducing the book, Witton writes authoritatively on the importance and aims of palaeoart, the difficulties of reconstructing species with limited fossil evidence, the limits of speculation and the tendency for palaeoart to predominantly focus on dinosaurs.

The huge number of images found in the book, which are often used to illustrate Witton’s technical explanations, make this book a real pleasure to flick through. There seems to be at least one illustration, often several, on almost every one of the book’s 200-plus pages, along with helpful diagrams showing how a small fossil feature has been interpreted by a palaeontologist or palaeoartist.

The book is packed with beautiful and varied artwork, from Raven Amos’ boldly coloured prints to Julius Csotonyi’s almost photorealistic scenes; from Rebecca Groom’s anatomically accurate plush toys to Witton’s own dramatic paintings and sculptures.

As well as being an invaluable guide for palaeoartists, this would be an enjoyable and informative read for those with a general interest in palaeontology or the interface between science and art.

Tom Ireland MRSB